Classification

Last updated on 2024-11-04 | Edit this page

Download Chapter notebook (ipynb)

Mandatory Lesson Feedback Survey

Overview

Questions

- How to prepare data for classification?

- Why do we need to train a model?

- What does a state space plot represent?

- How to obtain prediction probabilities?

- What are the important features?

Objectives

- Understanding the classification challenge.

- Training a classifier model.

- Understanding the state space plot of model predictions.

- Obtaining prediction probabilities.

- Finding important features.

Example: Visual Classification

Import the ‘patients_data’ toy dataset and scatter the data for Height and Weight.

PYTHON

# Please adjust your path to the file

df = read_csv('data/patients_data.csv')

print(df.shape)

# Convert inches to cm and pounds to kg:

df['Height'] = 2.540*df['Height']

df['Weight'] = 0.454*df['Weight']

df.head(10)OUTPUT

(100, 7)

Age Height Weight Systolic Diastolic Smoker Gender

0 38 180.34 79.904 124 93 1 Male

1 43 175.26 74.002 109 77 0 Male

2 38 162.56 59.474 125 83 0 Female

3 40 170.18 60.382 117 75 0 Female

4 49 162.56 54.026 122 80 0 Female

5 46 172.72 64.468 121 70 0 Female

6 33 162.56 64.468 130 88 1 Female

7 40 172.72 81.720 115 82 0 Male

8 28 172.72 83.082 115 78 0 Male

9 31 167.64 59.928 118 86 0 FemaleNote that data in the first five columns are either integers (age) or real numbers (floating point). The classes (categorical data) in the last two columns come as binary (0/1) for ‘smokers/non-smokers’ and as strings for ‘male/female’. Both can be used for classification.

The classification challenge

I am given a set of data from a single subject and feed them to a computational model. The model then predicts to what (predefined) class this subject belongs. Example: given height and weight data, the model might try to predict whether the subject is a smoker or a non-smoker. A naive model will, of course, not be able to predict reasonably. The supervised approach in machine learning is to provide the model with a set of data where the class has been verified beforehand and the model can test its (initially random) predictions against the provided class. An optimisation algorithm is then run to adjust the (internal) model setting such that the predictions improve as much as possible. When no further improvement is achieved, the algorithm stops. The model is then trained and ready to predict.

The act of classification is to assign labels to unlabelled data after model exposure to previously labelled data (e.g. based on medical knowledge in the case of disease data).

In contrast, in unsupervised machine learning the assignment is done based on exposure to unlabelled data following a search for distinctive features or ‘structure’ in the data.

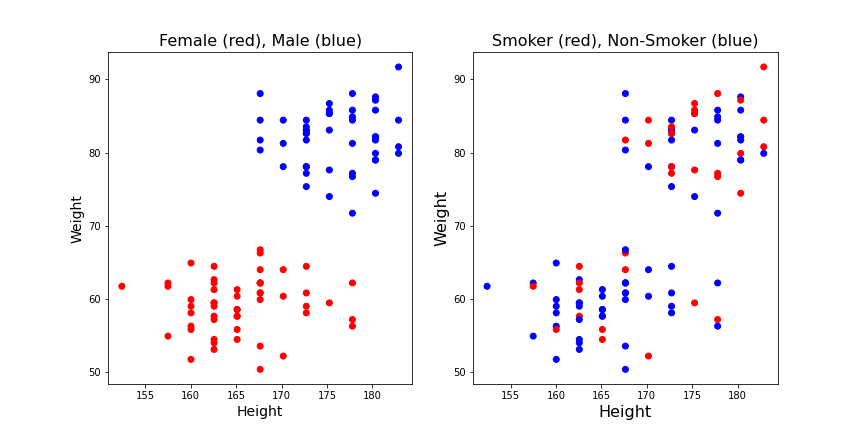

We can first check if we are able to distinguish classes visually. For this, we scatter the data of two columns of a dataframe using the column names. That is, we look at the distribution of points in a plane. Then we use the class label to color each point in the plane according to the class it belongs to. String labels like ‘male’ / ‘female’ first need to be converted to Boolean (binary). 0/1 labels as in the ‘smokers/non-smokers’ column can be used directly.

Let us plot the height-weight data and label them for both cases.

PYTHON

fig, ax = subplots(figsize=(12,6),ncols=2,nrows=1)

gender_boolean = df['Gender'] == 'Female'

ax[0].scatter(df['Height'], df['Weight'], c=gender_boolean, cmap='bwr')

ax[0].set_xlabel('Height', fontsize=14)

ax[0].set_ylabel('Weight', fontsize=14)

ax[0].set_title('Female (red), Male (blue)', fontsize=16)

ax[1].scatter(df['Height'], df['Weight'], c=df['Smoker'], cmap='bwr')

ax[1].set_xlabel('Height', fontsize=16)

ax[1].set_ylabel('Weight', fontsize=16)

ax[1].set_title('Smoker (red), Non-Smoker (blue)', fontsize=16);

show()

It appears from these graphs that based on height and weight data it is possible to distinguish male and female. Based on visual inspection one could conclude that everybody with a weight lower than 70kg is female and everybody with a weight above 70kg is male. That would be a classification based on the weight alone. It also appears that the data points classified as ‘male’ are taller on average, so it might be helpful to have the height recorded as well. E.g it could improve the prediction of gender for new subjects with a weight around 70 kg. But it would not be the best choice if only a single quantity was used. Thus, a second conclusion is that based on these data the weight is more important for the classification than the height.

On the other hand, based on the smoker / non-smoker data it will not be possible to distinguish smokers from non-smokers. Red dots and blue dots are scattered throughout the graph. The conclusion is that height and weight cannot be used to predict whether a subject is a smoker.

Supervised Learning: Training a Model

This lesson deals with labelled data. Labelled data are numerical data with an extra column of a label for each sample. A sample can consist of any number of individual observations but must be at least two.

Examples of labels include ‘control group / test group’; ‘male / female’; ‘healthy / diseased’; ‘before treatment / after treatment’.The task in Supervised Machine Learning is to fit (train) a model to distinguish between the groups by ‘learning’ from so-called training data. After training, the optimised model automatically labels incoming (unlabeled) data. The better the model, the better the labelling (prediction).

The model itself is a black box. It has set default parameters to start with and thus performs badly in the beginning. Essentially, it starts by predicting a label at random. The process of training consists in repeatedly changing the model parameters such that the performance improves. After the training, the model parameters are supposed to be optimal. Of course, the model cannot be expected to reveal anything about the mechanism or cause that underlies the distinction between the labels.

The performance of the model is tested by splitting a dataset with labels into:

the

train data, those that will be used for model fitting, andthe

test data, those that will be used to check how well the model predicts.

The result of the model fitting is then assessed by checking how many of the (withheld) labels in the test data were correctly predicted by the trained model. We can also retrieve the confidence of the model prediction, i.e. the probability that the assigned label is correct.

As an additional result, the procedure will generate the so-called feature importances: similar to how we concluded above that weight is more important than height for gender prediction, the feature importance informs to which degree each of the data columns actually contributes to the predictions.

Scikit Learn

We will import our machine learning functionality from the SciKit Learn library.

SciKit Learn

SciKit Learn is a renowned open source application programming interface (API) for machine learning. It enjoys a vibrant community and is well maintained. It is always beneficial to use the official documentations for every API. SciKit Learn provides an exceptional documentation with detailed explanations and examples at every level.

The implementation of algorithms in SciKit Learn follows a very specific protocol. First and foremost, it uses a programming paradigm known as object-oriented programming (OOP). Thanks to Python, this does not mean that you as the user are also forced to use OOP. But you need to follow a specific protocol to use the tools that are provided by SciKit Learn.

Unlike functions that perform a specific task and return the results, in

OOP, we use classes to encapsulate interconnected components

and functionalities. In accordance with the convention of best practices

for Python programming (also known as PEP8), classes are implemented

with camel-case characters; e.g. RandomForestClassifier. In

contrast, functions should be implemented using lower-case characters

only; e.g. min or round.

Classification

Prepare data with labels

The terminology that is widely used in Machine Learning (including

Scikit Learn) refers to data points as samples, and the

different types of recordings(columns in our case) are referred to as

features. In Numpy notation, samples are

organised in rows, features in columns.

We can use the function uniform from numpy.random to

generate uniformly distributed random data. Here we create 100 samples

of two features (as in the visualisation above). We decide to have

values distributed between 0 and 100.

The convention in machine learning is to call the training data ‘X’. This array must be two dimensional, where rows are the samples and columns are the features.

PYTHON

low = 0

high = 100

n_samples, m_features = 100, 2

RANDOM_SEED = 1234

seed(RANDOM_SEED)

random_numbers = uniform(low=low, high=high, size=(n_samples, m_features))

X = random_numbers.round(3)

print('Dimensions of training data')

print('')

print('Number of samples: ', X.shape[0])

print('Number of features: ', X.shape[1])

print('')OUTPUT

Dimensions of training data

Number of samples: 100

Number of features: 2Note

This code uses a random number generator. The output of

a random number generator is different each time it is run. On the one

hand, this is good because it allows us to create many realisations of

samples drawn from a fixed distribution. On the other hand, when testing

and sharing code this prevents exact reproduction of results. We

therefore use the seed function to reset the generator such

that with a given number for the seed (the parameter called

RANDOM_SEED) the same numbers are produced.

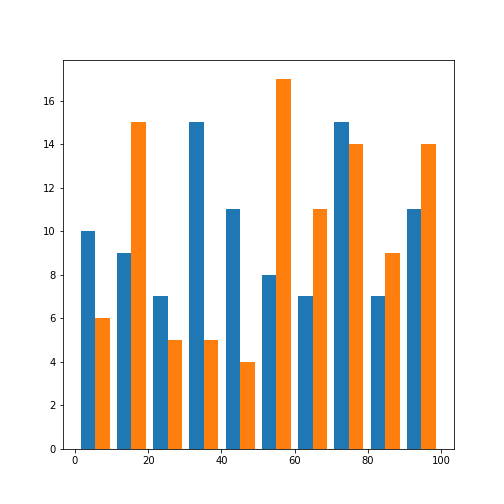

Let us check the histograms of both features:

We find that both features are distributed over the selected range of values. Due to the small number of samples, the distribution is not very even.

The categorical data used to distinguish between different classes are called labels. Let us create an artificial set of labels for our first classification task.

We pick an arbitrary threshold and call all values True if

the values in both the first and the second feature are above the

threshold. The resulting labels True and False

can be viewed as 0/1 using the method astype with argument

int.

OUTPUT

array([0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0,

1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1,

0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0,

0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1])If both features (columns) were risk factors, this might be interpreted as: only if both risk factors are above the threshold, a subject is classified as ‘at risk’, meaning it gets label ‘True’ or ‘1’.

Labels must be one-dimensional. You can check this

by printing the shape. The output should be a single

number:

OUTPUT

Number of labels: (100,)The Random Forest Classifier

To start with our learning algorithm, we import one of the many classifiers from Scikit Learn: it is called Random Forest.

The Random Forest is a member of the ensemble learning family, whose objective is to combine the predictions of several optimisations to improve their performance, generalisability, and robustness.

Ensemble methods are often divided into two different categories:

Averaging methods: Build several estimators independently, and average their predictions. In general, the combined estimator tends to perform better than any single estimator due to the reduction in variance. Examples: Random Forest and Decision Tree.

Boosting methods: Build the estimators sequentially, and attempt to reduce the bias of the combined estimator. Although the performance of individual estimators may be weak, upon combination, they amount to a powerful ensemble. Examples: Gradient Boosting and AdaBoost.

We now train a model using the Python class for the Random Forest classifier. Unlike a function (which we can use out of the box) a class needs to be instantiated before it can be used. In Python, we instantiate a class as follows:

where clf now represents an instance of class

RandomForestClassifier. Note that we have set the keyword

argument random_state to a number. This is to assure

reproducibility of the results. (It does not have to be the same as

above, pick any integer).

The instance of a class is typically referred to as an object, whose type is the class that it represents:

OUTPUT

Type of clf: <class 'sklearn.ensemble._forest.RandomForestClassifier'>

Once instantiated, we can use this object, clf, to access

the methods that are associated with that class. Methods are essentially

functions that are encapsulated inside a class.

In SciKit Learn all classes have a .fit() method. Its

function is to receive the training data and perform the training of the

model.

Train a model

To train a model, we apply the fit method to the training data, labelled ‘X’, given the corresponding labels ‘y’:

RandomForestClassifier(random_state=1234)In a Jupyter environment, please rerun this cell to show the HTML representation or trust the notebook.

On GitHub, the HTML representation is unable to render, please try loading this page with nbviewer.org.

RandomForestClassifier(random_state=1234)

And that’s it. All the machine learning magic done. clf

is now a trained model with optimised parameters which we can use to

predict new data.

Categorical Prediction

We start by creating a number of test data in the same way as we created the training data. Note that the number of test samples is arbitrary. You can create any number of samples. However, you must provide the same number of features (columns) used in the training of the classifier. In our case that is 2.

PYTHON

RANDOM_SEED_2 = 123

seed(RANDOM_SEED_2)

new_samples = 10

features = X.shape[1]

new_data = uniform(low=low, high=high, size=(10, 2))

print('Shape of new data', new_data.shape)

print('')

print(new_data)OUTPUT

Shape of new data (10, 2)

[[69.64691856 28.6139335 ]

[22.68514536 55.13147691]

[71.94689698 42.31064601]

[98.07641984 68.48297386]

[48.09319015 39.21175182]

[34.31780162 72.90497074]

[43.85722447 5.96778966]

[39.80442553 73.79954057]

[18.24917305 17.54517561]

[53.15513738 53.18275871]]There are 10 randomly created pairs of numbers in the same range as the training data. They represent ‘unlabelled’ incoming data which we offer to the trained model.

The method .predict() helps us to find out what the

model claims these data to be:

OUTPUT

Predictions: [False False False True False False False False False True]They can also be viewed as zeros and ones:

OUTPUT

array([0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1])According to the model, data points with indices 3, and 9 are in

class True (or 1).

Predicting individual samples is fine, but does not tell us whether the classifier was able to create a good model of the class distinction. To check the training result systematically, we create a state space grid over the state space. This is the same as creating a coordinate system of data points (as in a scatter plot), in our case with values from 0 to 100 in each feature.

Here we use a resolution of 100, ie. we create a 100 by 100 grid:

PYTHON

resolution = 100

vec_a = linspace(low, high, resolution)

vec_b = vec_a

grid_a, grid_b = meshgrid(vec_a, vec_b)

grid_a_flat = grid_a.ravel()

grid_b_flat = grid_b.ravel()

XY_statespace = c_[grid_a_flat, grid_b_flat]

print(XY_statespace.shape)OUTPUT

(10000, 2)Now we can offer the grid of the X-Y state space as ‘new data’ to the classifier and obtain the predictions. We can then plot the grid points and colour them according to the labels assigned by the trained model.

OUTPUT

(10000,)We obtain 10,000 predictions, one for each point on the grid.

To compare the data with the original thresholds and the model predictions we can use plots of the state space:

PYTHON

feature_1, feature_2 = 0, 1

fig, ax = subplots(ncols=2, nrows=1, figsize=(10, 5))

ax[0].scatter(X[:, feature_1], X[:, feature_2], c=y, s=4, cmap='bwr');

ax[1].scatter(XY_statespace[:, feature_1], XY_statespace[:, feature_2], c=predictions, s=1, cmap='bwr');

p1, p2 = [threshold, threshold], [100, threshold]

p3, p4 = [threshold, 100], [threshold, threshold]

ax[0].plot(p1, p2, c='k')

ax[0].plot(p3, p4, c='k')

ax[0].set_xlabel('Feature 1', fontsize=16)

ax[0].set_ylabel('Feature 2', fontsize=16);

ax[1].set_xlabel('Feature 1', fontsize=16);

show()

Left is a scatter plot of the data points used for training. They are coloured according to their labels. The black lines indicate the threshold boundaries that we introduced to distinguish the two classes. On the right hand side are the predictions for the coordinate grid. Label 0 is blue, label 1 is red.

Based on the training samples (left), a good classification can be achieved with the model (right). But some problems persist. In particular, the boundaries are not sharp.

Probability Prediction

Let us pick a sample near the boundary. We can get its predicted label.

In addition, using .predict_proba() we can get the

probability of this prediction. This reflects the confidence in the

prediction. 50% probability means, the prediction is at chance level,

i.e. equivalent to a coin toss.

PYTHON

pos = 55

test_sample = [[pos, pos]]

test_sample_label = clf.predict(test_sample)

test_sample_proba = clf.predict_proba(test_sample)

print('Prediction:', test_sample_label)

print(clf.classes_, test_sample_proba)OUTPUT

Prediction: [False]

[False True] [[0.57 0.43]]PYTHON

bins = arange(test_sample_proba.shape[1])

fig, ax = subplots()

ax.bar(bins, test_sample_proba[0,:], color=('b', 'r'))

ax.set_ylabel('Probability', fontsize=16)

xticks(bins, ('Label 0', 'Label 1'), fontsize=16);

show()

Even though the sample is from the region that (according to the creation of the data) is in the ‘True’ region, it is labelled as false. The reason is that there were few or no training data points in that specific region.

Here is a plot of the probability for the state space. White represents False and Black represents True, the values in between are gray coded. Note that the probability values are complementary. We only need the probabilities for one of our classes.

PYTHON

state_space_proba = clf.predict_proba(XY_statespace)

grid_shape = grid_a.shape

proba_grid = state_space_proba[:, 1].reshape(grid_shape)

contour_levels = linspace(0, 1, 6)

fig, ax = subplots(figsize=(6, 5))

cax = ax.contourf(grid_a, grid_b, proba_grid, cmap='Greys', levels=contour_levels)

fig.colorbar(cax)

ax.scatter(test_sample[0][0], test_sample[0][1], c='r', marker='o', s=100)

ax.plot(p1, p2, p3, p4, c='r')

ax.set_xlabel('Feature 1', fontsize=16)

ax.set_ylabel('Feature 2', fontsize=16);

show()

The single red dot marks the individual data point we used to illustrate the prediction probability above.

Feature Importances

We can check the contribution of each feature for the success of the classification. The feature importance is given as the fraction contribution of each feature to the prediction.

PYTHON

importances = clf.feature_importances_

print('Relative importance:')

template = 'Feature 1: {:.1f}%; Feature 2: {:.1f}%'

print(template.format(importances[0]*100, importances[1]*100))

bins = arange(importances.shape[0])

fig, ax = subplots()

ax.bar(bins, importances, color=('g', 'm'));

ax.set_ylabel('Feature Importance', fontsize=16)

xticks(bins, ('Feature 1', 'Feature 2'), fontsize=16);

show()OUTPUT

Relative importance:

Feature 1: 61.6%; Feature 2: 38.4%

In this case, the predictions are based on a 61% contribution from feature 1 and a 38% contribution from feature 2.

Application

Now we pick the ‘Height’ and ‘Weight’ columns from the patients data to predict the gender labels. We use a split of 4/5 of the data for training and 1/5 for testing.

PYTHON

df = read_csv('data/patients_data.csv')

print(df.shape)

# Convert pounds to kg and inches to cm:

df['Weight'] = 0.454*df['Weight']

df['Height'] = 2.540*df['Height']

df.head(10)OUTPUT

(100, 7)

Age Height Weight Systolic Diastolic Smoker Gender

0 38 180.34 79.904 124 93 1 Male

1 43 175.26 74.002 109 77 0 Male

2 38 162.56 59.474 125 83 0 Female

3 40 170.18 60.382 117 75 0 Female

4 49 162.56 54.026 122 80 0 Female

5 46 172.72 64.468 121 70 0 Female

6 33 162.56 64.468 130 88 1 Female

7 40 172.72 81.720 115 82 0 Male

8 28 172.72 83.082 115 78 0 Male

9 31 167.64 59.928 118 86 0 FemalePrepare training data and labels

PYTHON

# Extract data as numpy array

df_np = df.to_numpy()

# Pick a fraction of height and weight data as training data

samples = 80

X = df_np[:samples, [1, 2]]

print(X.shape)OUTPUT

(80, 2)For the labels of the training data we convert the ‘Male’ and ‘Female’ strings to categorical values.

PYTHON

gender_boolean = df['Gender'] == 'Female'

y = gender_boolean[:80]

# printed as 0 and 1:

y.astype('int')OUTPUT

0 0

1 0

2 1

3 1

4 1

..

75 0

76 1

77 0

78 0

79 1

Name: Gender, Length: 80, dtype: int64Train classifier and predict

PYTHON

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifier

seed(RANDOM_SEED)

clf = RandomForestClassifier(random_state=RANDOM_SEED)

clf.fit(X, y)RandomForestClassifier(random_state=1234)In a Jupyter environment, please rerun this cell to show the HTML representation or trust the notebook.

On GitHub, the HTML representation is unable to render, please try loading this page with nbviewer.org.

RandomForestClassifier(random_state=1234)

We now take the remaining fifth of the data to predict.

PYTHON

X_test = df.loc[80:, ['Height', 'Weight']]

X_test = X_test.values

predict_test = clf.predict(X_test)

probab_test = clf.predict_proba(X_test)

print('Predictions: ', predict_test, '\n', 'Probabilities: ', '\n', probab_test)OUTPUT

Predictions: [False False False True True False True True True True False False

True False True False False False False False]

Probabilities:

[[1. 0. ]

[1. 0. ]

[1. 0. ]

[0. 1. ]

[0. 1. ]

[1. 0. ]

[0. 1. ]

[0. 1. ]

[0. 1. ]

[0. 1. ]

[1. 0. ]

[1. 0. ]

[0.02 0.98]

[1. 0. ]

[0. 1. ]

[1. 0. ]

[1. 0. ]

[1. 0. ]

[1. 0. ]

[0.97 0.03]]As in the example above, we create a state space grid to visualise the outcome for the two features.

PYTHON

X1_min, X1_max = min(X[:, 0]), max(X[:, 0])

X2_min, X2_max = min(X[:, 1]), max(X[:, 1])

resolution = 100

vec_a = linspace(X1_min, X1_max, resolution)

vec_b = linspace(X2_min, X2_max, resolution)

grid_a, grid_b = meshgrid(vec_a, vec_b)

grid_a_flat = grid_a.ravel()

grid_b_flat = grid_b.ravel()

X_statespace = c_[grid_a_flat, grid_b_flat]We can now obtain the categorical and probability predictions from the trained classifier for all points of the grid.

Here is the plot of the state space and the predicted probabilities:

PYTHON

feature_1, feature_2 = 0, 1

fig, ax = subplots(ncols=3, nrows=1, figsize=(15, 5))

ax[0].scatter(X[:, feature_1], X[:, feature_2], c=y, s=40, cmap='bwr');

ax[0].set_xlim(X1_min, X1_max);

ax[0].set_ylim(X2_min, X2_max);

ax[0].set_xlabel('Feature 1', fontsize=16);

ax[0].set_ylabel('Feature 2', fontsize=16);

cax1 = ax[1].scatter(X_statespace[:, feature_1], X_statespace[:, feature_2], c=predict, s=1, cmap='bwr');

ax[1].scatter(X_test[:, feature_1], X_test[:, feature_2], c=predict_test, s=40, cmap='Greys');

ax[1].set_xlabel('Feature 1', fontsize=16);

ax[1].set_xlim(X1_min, X1_max);

ax[1].set_ylim(X2_min, X2_max);

fig.colorbar(cax1, ax=ax[1]);

grid_shape = grid_a.shape

probab_grid = probabs[:, 1].reshape(grid_shape)

# Subject with 170cm and 70 kg

pos1, pos2 = 170, 70

test_sample = [pos1, pos2]

contour_levels = linspace(0, 1, 10)

cax2 = ax[2].contourf(grid_a, grid_b, probab_grid, cmap='Greys', levels=contour_levels);

fig.colorbar(cax2, ax=ax[2]);

ax[2].scatter(test_sample[0], test_sample[1], c='r', marker='o', s=100);

ax[2].set_xlabel('Feature 1', fontsize=16);

ax[2].set_xlim(X1_min, X1_max);

ax[2].set_ylim(X2_min, X2_max);

show()

The left panel shows the original data with labels as colours, i.e. the training data. Central panel shows the classified state space with the test samples as black dots in predicted category ‘Female’ and white dots in predicted category ‘Male’. Right panel shows the state space with prediction probabilities with black for ‘Female’ and white for ‘Male’. The red dot represents the simulated subject with 170cm and 70 kg (see below).

Probability of a single observation

Let us pick that subject and obtain its predicted label and probability. Note the use of double brackets to create a sample that is a two-dimensional array.

PYTHON

test_sample = [[pos1, pos2]]

test_predict = clf.predict(test_sample)

test_proba = clf.predict_proba(test_sample)

print('Predicted class:', test_predict, 'Female')

print('Probability:', test_proba[0, 0])

print('')

bins = arange(test_proba.shape[1])

fig, ax = subplots()

ax.bar(bins, test_proba[0,:], color=('r', 'b'));

xticks(bins, ('Female', 'Male'), fontsize=16);

ax.set_ylabel('Probability', fontsize=16);

show()OUTPUT

Predicted class: [False] Female

Probability: 0.66

This shows that the predicted label is female but the probability is less than 70 % and, e.g. if a clinical decision was to be taken based on the outcome of the classification, it might suggest looking for additional evidence before the decision is made.

Feature Importances

PYTHON

importances = clf.feature_importances_

print('Features importances:')

template = 'Feature 1: {:.1f}%; Feature 2: {:.1f}%'

print(template.format(importances[0]*100, importances[1]*100))

print('')

bins = arange(importances.shape[0])

fig, ax = subplots()

ax.bar(bins, importances, color=('m', 'g'));

xticks(bins, ('Feature 1', 'Feature 2'), fontsize=16);

ax.set_ylabel('Feature Importance', fontsize=16);

show()OUTPUT

Features importances:

Feature 1: 31.7%; Feature 2: 68.3%

Feature importances can be used in data sets with many features, e.g. to reduce the number of features used for classification. Some features might not contribute to the classification and could therefore be left out of the process.

In the next lesson, we are going to test multiple classifiers and quantify their performance to improve the outcome of the classification.

Exercises

End of chapter Exercises

Repeat the training and prediction workflow as above for two other features in the data, namely: Systole and Diastole values. Use 70 training and 30 testing samples where the labels are assigned according to the condition: 0 if ‘non-smoker’, 1 if ‘smoker’.

Use the above code to:

Train the random forest classifier.

Create state space plots with scatter plot, categorical colouring, and probability contour plot.

Compare the predicted and actual labels to check how well the trained model performed: how many of the 30 test data points are correctly predicted?

Plot the feature importance to check how much the systolic and diastolic values contributed to the predictions.

Further Practice: Iris data

You can try to use the Random Forest classifier on the Iris data:

The Iris data are a collection of five features (sepal length, sepal width, petal length, petal width and species) from 3 species of Iris (Iris setosa, Iris virginica and Iris versicolor). The species name is used for training in classification.

Import the data from scikit-learn as:

PYTHON

from sklearn import datasets

# Import Iris data

iris = datasets.load_iris()

# Get first two features and labels

X = iris.data[:, :2]

y = iris.target

print(X.shape, y.shape)OUTPUT

(150, 2) (150,)Key Points

- Classification is to assign labels to unlabeled data.

-

SciKit Learnis an open source application programming interface (API) for machine learning. -

.fit()function is used to receive the training data and perform the training of the model. -

.predict()function helps to find out what the model claims these data to be. -

.predict_proba()function predicts the probability of any predictions.