Variables, Types, and Operations

Last updated on 2024-08-05 | Edit this page

Download Chapter notebook (ipynb)

Mandatory Lesson Feedback Survey

Overview

Questions

- What are input and output (I/O) operations?

- What do variables do?

- Why are types and scopes of variables important?

- What types of operations are used?

Objectives

- Understanding I/O operations

- Build concepts of different types of variables

- Learning about type conversions and scope

- Understanding mathematical and logical operations

In programming, we process data and produce outputs. When data is being processed, it is stored in memory so that it is readily available, and can therefore be subject to the processes we want to apply.

In this lesson, we will discuss how to handle data in Python. We will start by displaying data on the screen, and understand how to receive input from a user. We can then use these techniques to perform different mathematical and logical operations. We will also cover the fundamental principles employed every time we code in Python. It is imperative that you understand everything before moving on.

I/O Operations

In computer science, input or output operations refer to the communication between an information processing system such as a computer, and the outside world, which may be a user or even another computer. Such communications are more commonly known as I/O operations. In general, this ‘outside world’ may be loosely defined as anything that falls outside of the coding environment.

REMEMBER

Only what we define within the environment and what we store in the memory is directly controlled by our application. We may access or take control over other environments, however, these interactions are classified as I/O operations. An example of this is interacting with a file on our computer. While we have complete control over a file while working on it (e.g. reading from it or writing to it), the access to the file and the transmission of data is in fact controlled and managed not by the programming environment but by the operating system of the computer.

In programming, I/O operations include, but are not limited to:

Displaying the results of a calculation

Requiring the user to enter a value

Writing or reading data to and from a file or a database

Downloading data from the Internet

Operating a hardware (such as a robot, for example)

Advanced Topic

If you are interested in learning more about I/O systems and how they are handled at operating system level, you might benefit from chapter 13 of Operating Systems Concepts, 10th ed. by Abraham Silberschatz, Greg Gagne, and Peter Galvin.

I/O Operations in Python

In this section, we learn about two fundamental methods of I/O operations in Python. We will be using these methods throughout the course, so it is essential that you feel comfortable with them and the way they work before moving on.

Producing an output

The term output in reference to an application typically

refers to data that has either been generated or manipulated by that

application.

For example; calculating the sum of two numbers. The action of

calculating the sum is itself a mathematical

operation. The result of our calculation is called its

output. Once we obtain the result, we might want to save it

in a file or display it on the screen, in which case we will be

performing an I/O operation. I/O operation.

The simplest and most frequently used method for generating output in almost every modern programming language is to display something on the screen. We recommend using Jupyter Notebooks to run our Python scripts, which defaults to displaying the output of a code cell beneath the code itself. We will start by calling a dedicated built-in function named print().

REMEMBER

In programming, a function is essentially an isolated piece

of code. It usually accepts input, does something to or with

this, and produces output. A function can process input,

often using several operations in a particular sequence or

configuration, and process the input to give a final output. In Python

programming syntax, a pair of (typically round) parentheses follows a

function, and these provide the function with the input

arguments it needs when we call it, so that it can do what

we intend, to our data. We will explore functions in more details in

Basic Python 4: Functions.

The print() function can take several inputs and performs different tasks. Its primary objective, however, is to take some values as input and display them on the screen. Here is how it works:

Suppose we want to display some text in the Terminal. To do so, we write the following into a cell of our Jupyter Notebook (or on the Terminal, a code editor or dedicated Integrated Development Environment (IDE)):

print('Welcome to L2D!!!')This is now a fully functioning Python program that we can run using the Python interpreter.

If you are using an IDE (such as Mircosoft Visual Studio Code, for

example) you must save the code in a file with the extension

.py, in order to execute your code using the internal tools

provided by that IDE. The specifics of how you do so depend on the IDE

that you are using.

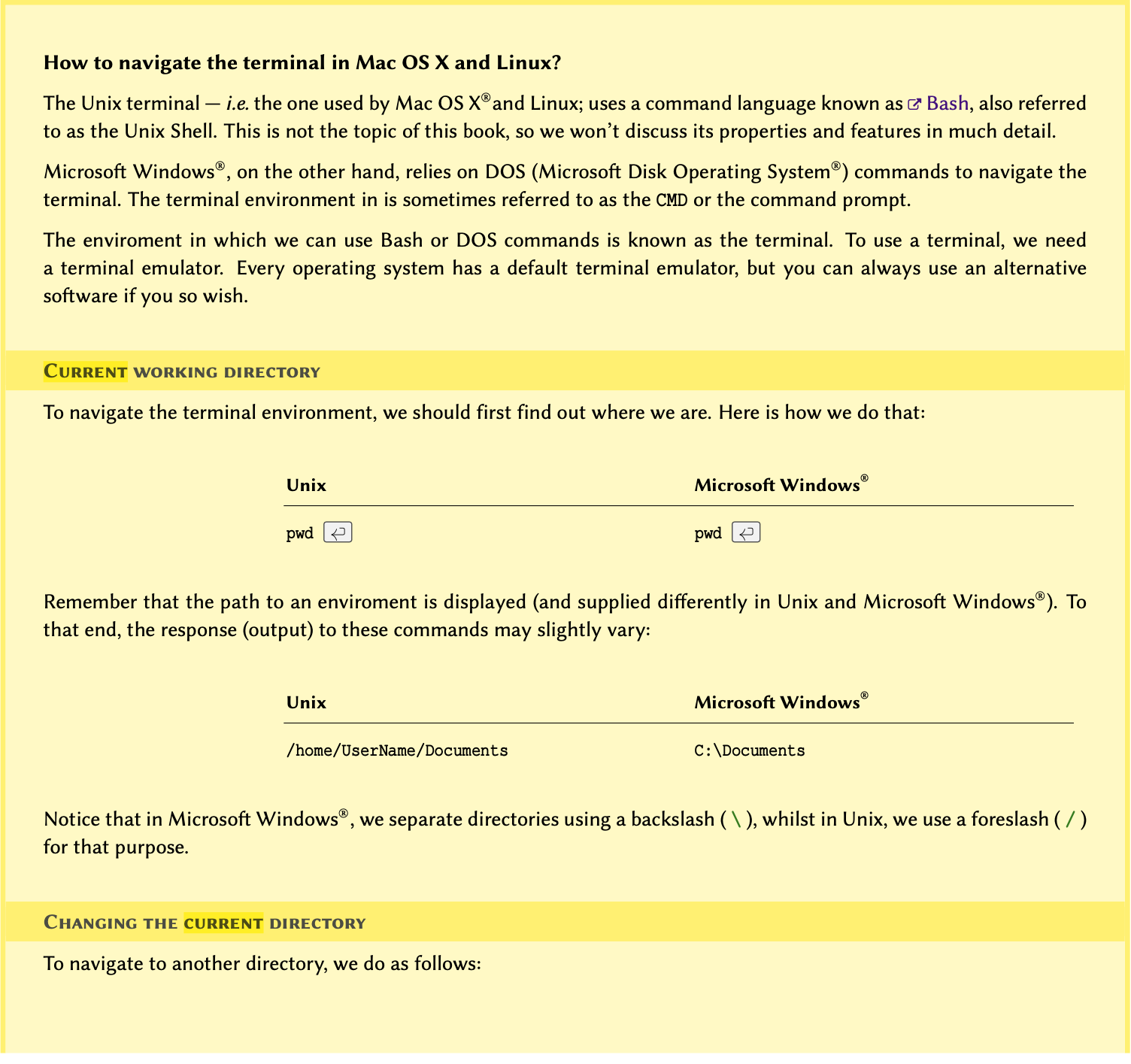

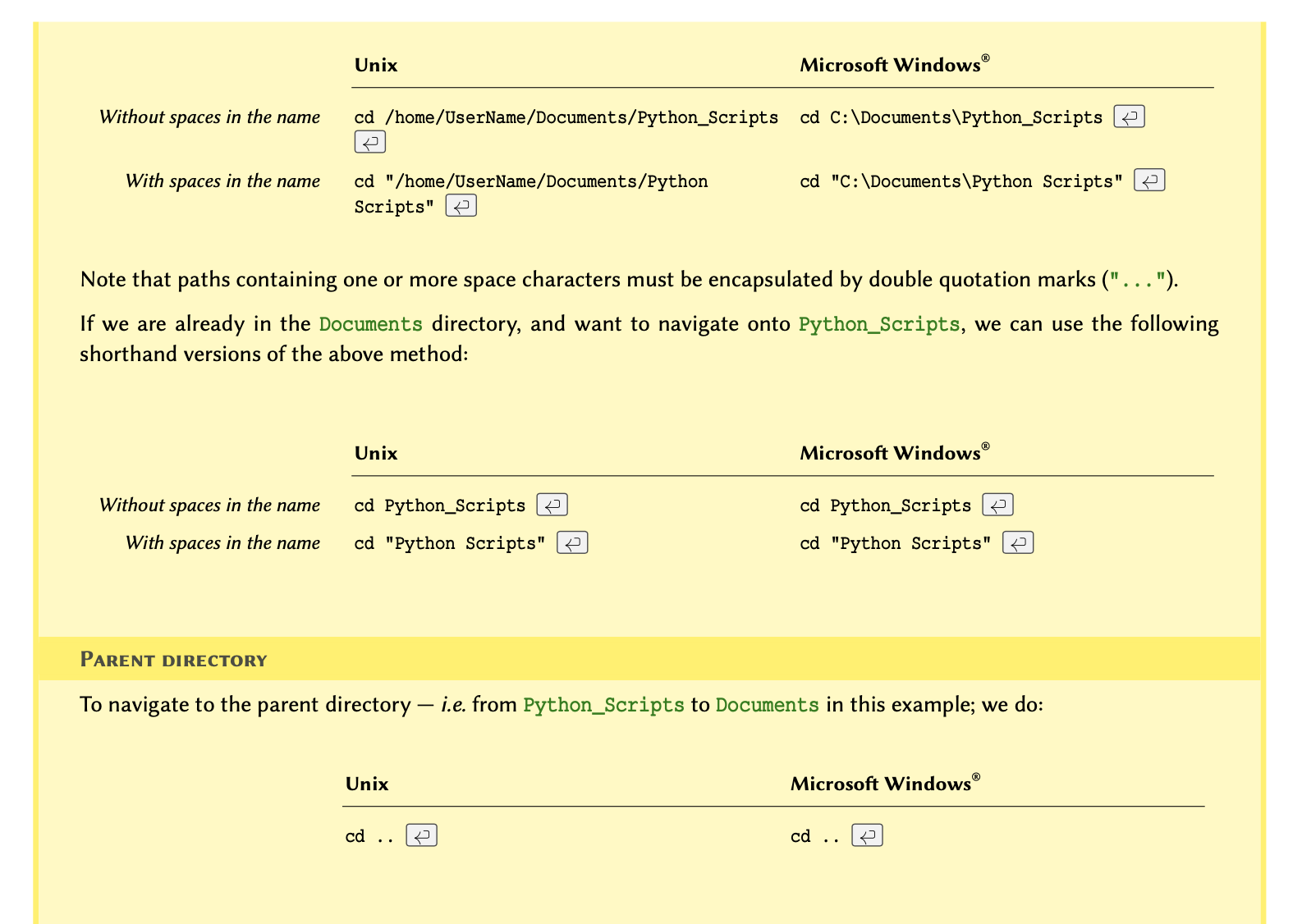

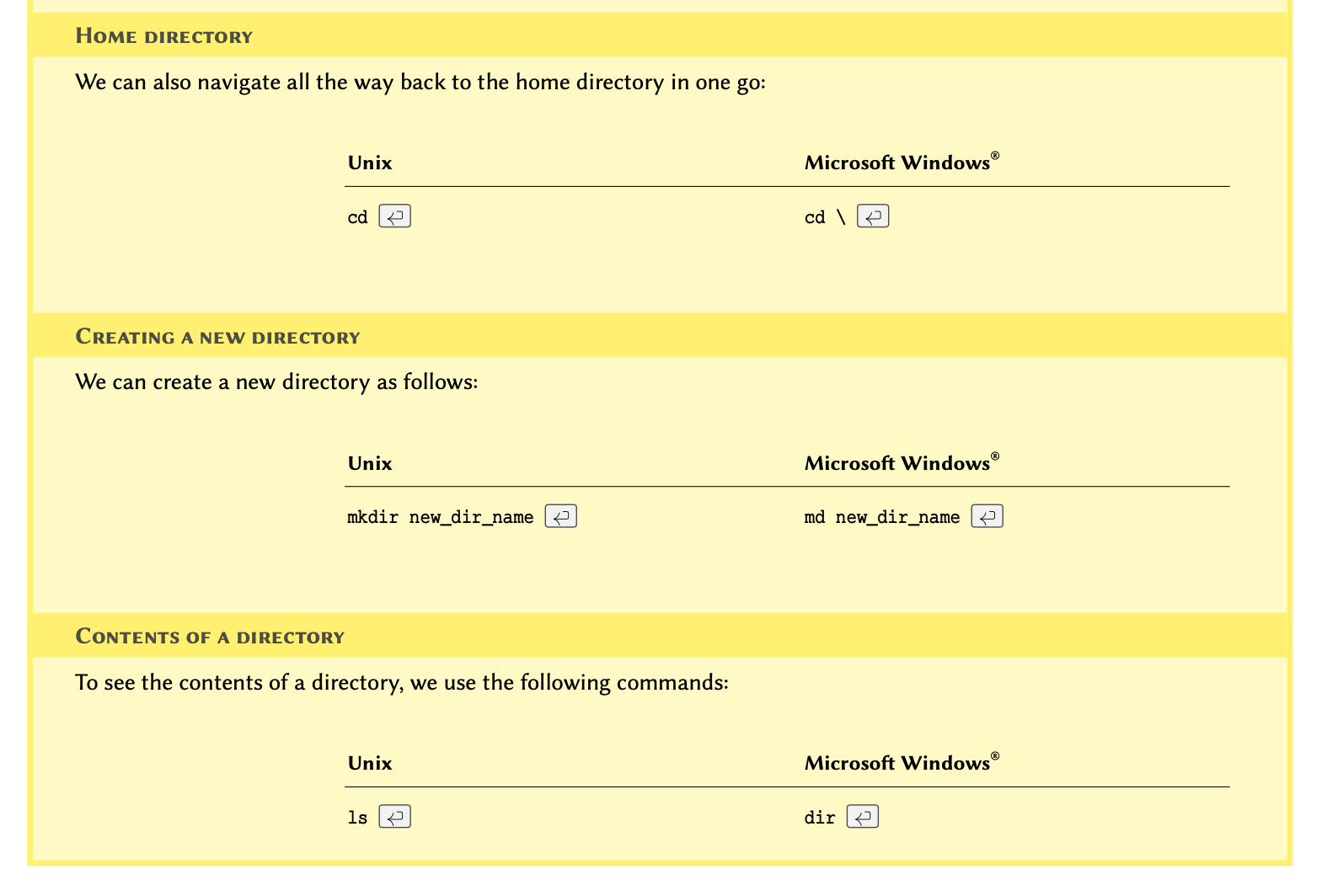

.py Python scripts can also be executed manually. To do so,

we open the Terminal in MacOS or Linux or the command prompt (CMD) in

Windows and navigate to the directory where we saved the script.

NOTE

If you don’t know how to navigate in the Terminal, see the example in section How to use terminal environment? at the end of this chapter.

Once in the correct directory, we run a script called

script_a.py by typing python3 script_a.py in

our Terminal as follows:

OUTPUT

Hello world!

This will call the Python 3 interpreter to execute the code we wrote in

script_a.py. Once executed, we will see the output

displayed in the Terminal window.

In a Jupyter Notebook we can press the keyboard shortcut ‘shift+enter’ to execute the code in a cell. The output will be displayed below the code cell.

You have now successfully written and executed your first program in Python.

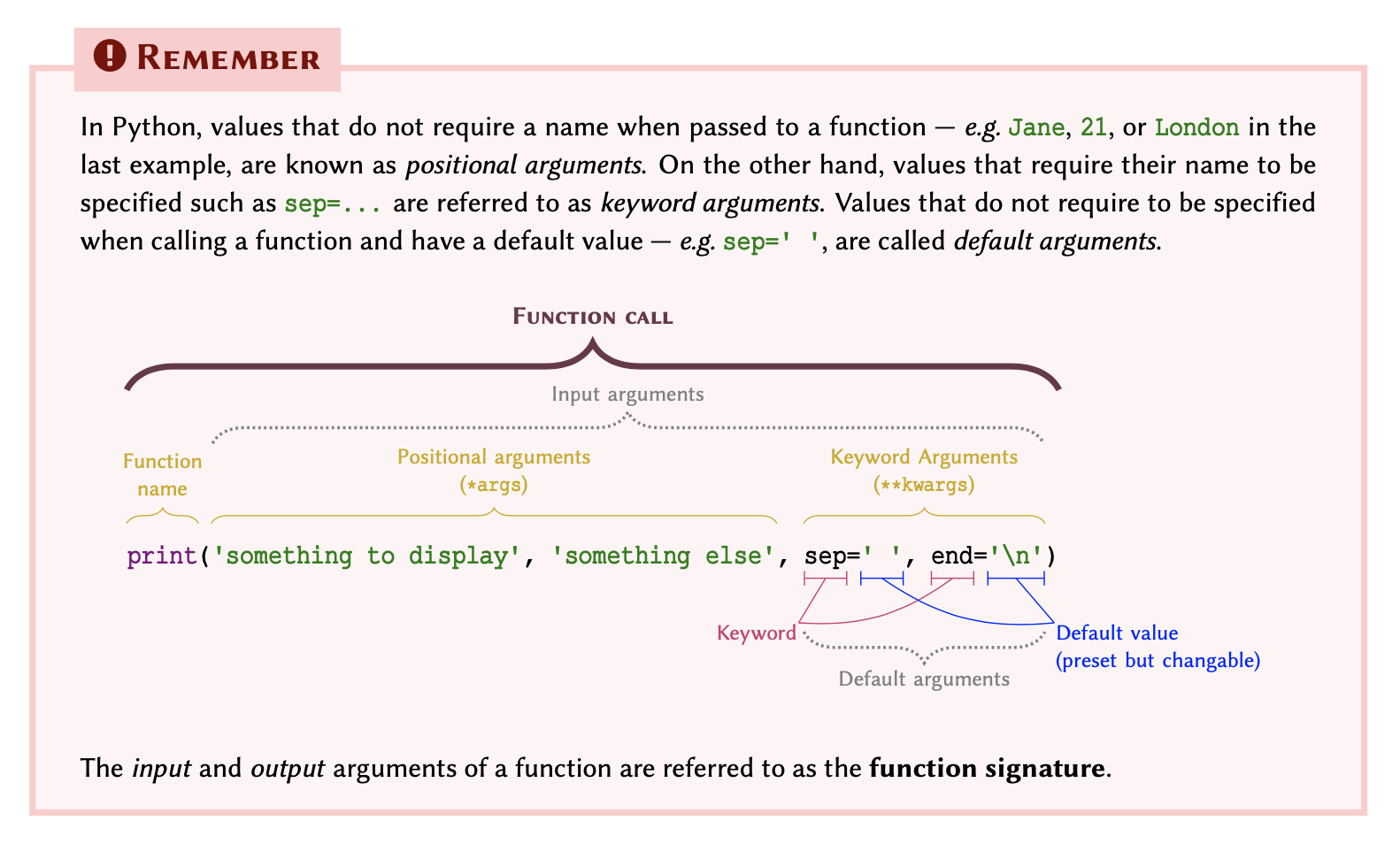

REMEMBER

We know that print() is a function because it ends with a pair of parentheses, and it is written entirely in lowercase characters PEP-8: Function Names. Some IDEs change color when they encounter built-in functions, in order to signal to the user that the function is recognised, and available to use, and so that we don’t accidentally overwrite them.

We can pass more than a single value to the print() function, provided that each value is separated from another, using a comma. For instance, if we write the code below and run the script, the results would be as shown in output.

OUTPUT

Hello JohnNotice that there is a space between ‘Hello’ and ‘John’ even though we did not include a space in our text. This is the default behaviour of the print() function when it receives more than a single value (argument).

This default behaviour may be changed using a keyword argument called sep:

OUTPUT

HelloJohnOUTPUT

Hello--JohnOUTPUT

Jane.21.London

Practice Exercise 1

Write code that displays the following output:

Protein Kinase C (Alpha subunit)

Receiving an input

Inputs are I/O operations that involve receiving some data from the outside world. This might include reading the contents of a file, downloading something from the internet, or asking the user to enter a value.

The simplest way to acquire an input is to ask the user to enter a value in the Terminal. To do so, we use a dedicated built-in function called input().

Note

In a Unix system (Mac OS or Linux), a tilde (~) is an alias that is used to refer to a user’s home directory.

This function takes a single argument called

prompt. Prompt is the text displayed in the Terminal to ask

the user for an input. Figure Terminal window on

a Linux computer and Terminal window on a

Mac, illustrates a screen shot of an example PC’s prompt, where it

displays a user name (i.e. pouria) followed by a tilde (~).

A Terminal prompt may be different in each computer and operating

system.

Here is how we implement the input() function:

input('Please enter your name: ')which is exactly the same as:

input(prompt='Please enter your name: ')If we save one of the above in a notebook and execute it, we will see:

python3 script_b.py

Please enter your name: _

The Terminal cursor, displayed as an underscore in our example, will be

in front of the prompt (i.e. 'Please enter your name: ')

waiting for a response. Once it receives a response, it will proceed to

run the rest of the code (if any), or terminate the execution.

We may store the user’s response in a variable. Variables are the topic of the next episode in this learning material, where we shall also review more examples on input() and how we can use it to produce results based on the responses we receive from the user.

Remember

Python is an interpreted language; this means that the code we write is executed by the Python interpreter one line at a time. The input() function performs a blocking process. This means that the execution of the code by the Python interpreter is halted upon encountering an input() function until the user enters a value. Once a value is entered, the interpreter then proceeds to execute the next line.

Practice Exercise 2

Write a script that asks the user to enter the name of a protein in the Terminal.

input('Please enter the name of a protein: ')Variables And Types

Variables are a type of data container, that we can use to store data to memory. Each variable has three main types of attribute: scope, name, and type. Scope and name must be mutually unique. Starting with name, we will discuss each of these attributes in more details throughout this chapter.

Variable names

The name that we give to a variable is, in fact, an alias for a location

in the memory. You can think of it as a postbox, which is used as a

substitute for an actual address. Similarly, we use variable names so we

don’t have to use the actual address to the location we want in the

memory; because it would look something like this

0x106fb8348.

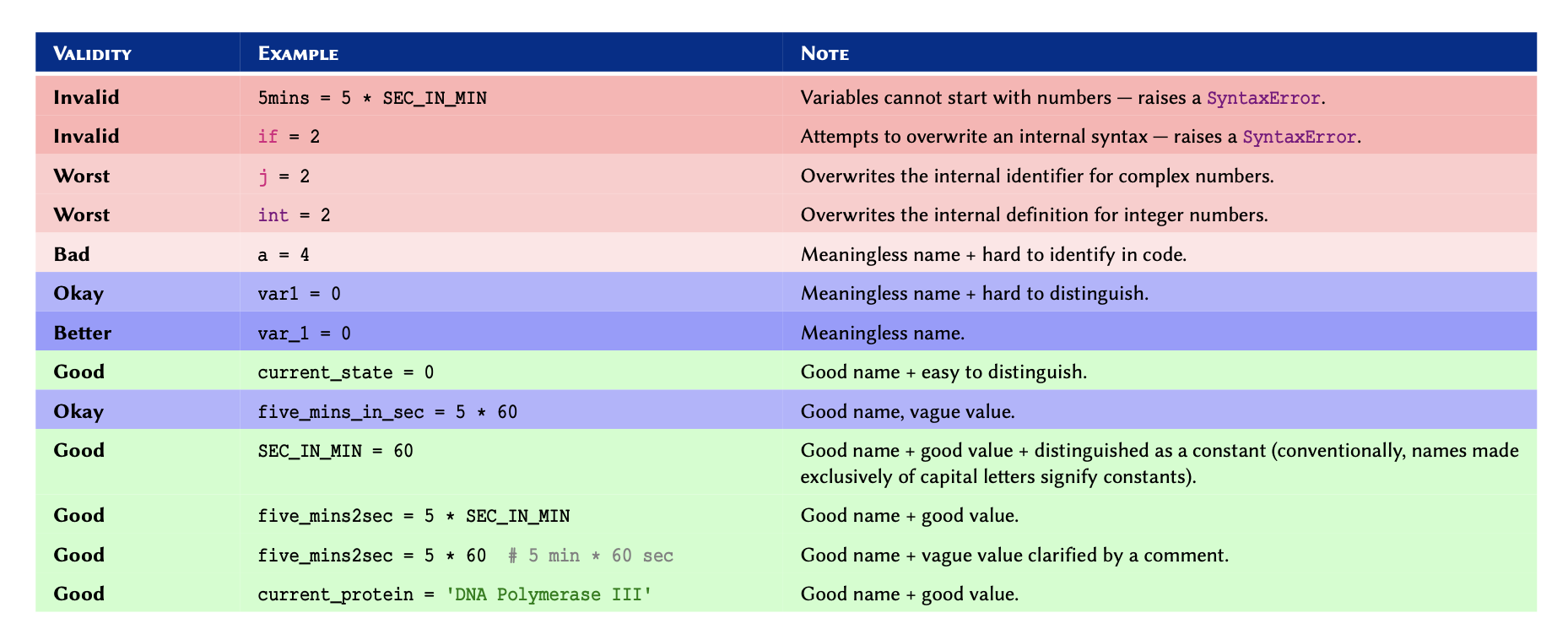

There are some relatively simple rules to follow when defining variable names, which ultimately boil down to:

Remember

We should never overwrite an existing, built-in definition or identifier

(e.g. int or print). We will be learning many

such definitions and identifiers as we progress through this course.

Nonetheless, the Jupyter Notebook as well as any good IDE highlights

syntaxes and built-in identifiers in different colours. In Jupyter, the

default for built-in definitions is green. The exact colouring scheme

depends on the IDE being used, and the selected theme.

Once a variable is defined, its value may be altered or reset:

OUTPUT

2In Python, variables containing integer numbers are referred to as

int, and those containing decimal numbers are referred to

as float.

OUTPUT

3OUTPUT

3.2OUTPUT

16.0

Variables can contain data as characters as well; but to prevent Python

from confusing them with meaningful commands, we use quotation marks. So

long as we remain consistent, it doesn’t matter whether we use

single or double quotations. These data are known as

string or str:

OUTPUT

Hi, John DoePractice Exercise 3

Oxidised low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor 1 mediates the recognition, internalisation and degradation of oxidatively modified low-density lipoprotein by vascular endothelial cells. Using the Universal Protein Resource (UniProt) website, find this protein for humans, and identify:

- UniProt entry number.

- Length of the protein (right at the top).

- Gene name (right at the top).

Store the information you retrieved, including the protein name, in within four separate variables.

Display the values of these four variables in one line, and separate the items with three spaces, as follows:

Name EntryNo GeneName Length

Practice Exercise 4

Write a Python code that upon execution, asks the user to enter the name of an enzyme and then stores the response in an appropriately named variable.

Use the variable to display an output similar to the following:

ENZYME_NAME is an enzyme.

where ENZYME_NAME is the name of the enzyme entered in

the prompt.

Now modify your script to prompt the user to enter the number of amino acids in that enzyme. Store the value in another appropriately named variable.

Alter the output of your script to display a report in the following format:

ENZYME_NAME is an enzyme containing a total number of AMINO_ACIDS} amino acids.

where AMINO_ACIDS is the number of amino acids.

enzyme = input('Please enter the name of an enzyme: ')

print(enzyme, 'is an enzyme.')

length = input('How many amino acids does the enzyme contain? ')

print(enzyme, 'is an enzyme containing a total number of', length, 'amino acids.')Variable Types

When it comes to types, programming languages may be divided into two distinct categories:

Types

Python is a dynamically typed language, and falls into this second category. This means that, unlike statically typed languages, we rarely need to worry about the type definitions because in the majority of cases, Python takes care of them for us, and automatically decodes the type of data being stored in a variable, once it is defined by the user.

Remember

In a dynamically typed language, it is the value of a variable that determines the type. This is because the types are determined on the fly by the Python interpreter as and when it encounters different variables and values.

Advanced Topic

In computer programming, type systems are syntactic methods to enforce and/or identify levels of abstraction. This means that type systems take advantage of the syntax of a particular programming language, in order to enforce rules and identify types. This is important, as it can manage abstraction in data, by ensuring that differing data types interact meaningfully with one another. An entire field in computer science has been dedicated to the study of programming languages from a type–theoretic approach. This is primarily due to the implication of types and their underlying principles in such areas in software engineering as optimisation and security. To learn more about the study of type systems, refer to: Pierce B. Types and programming languages. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press; 2002.

Note

The values determine the type of a variable in dynamically typed languages. This is in contrast to statically typed languages, where a variable must be initialised using a specific type before a value.

Why learn about types in a dynamically typed programming language?

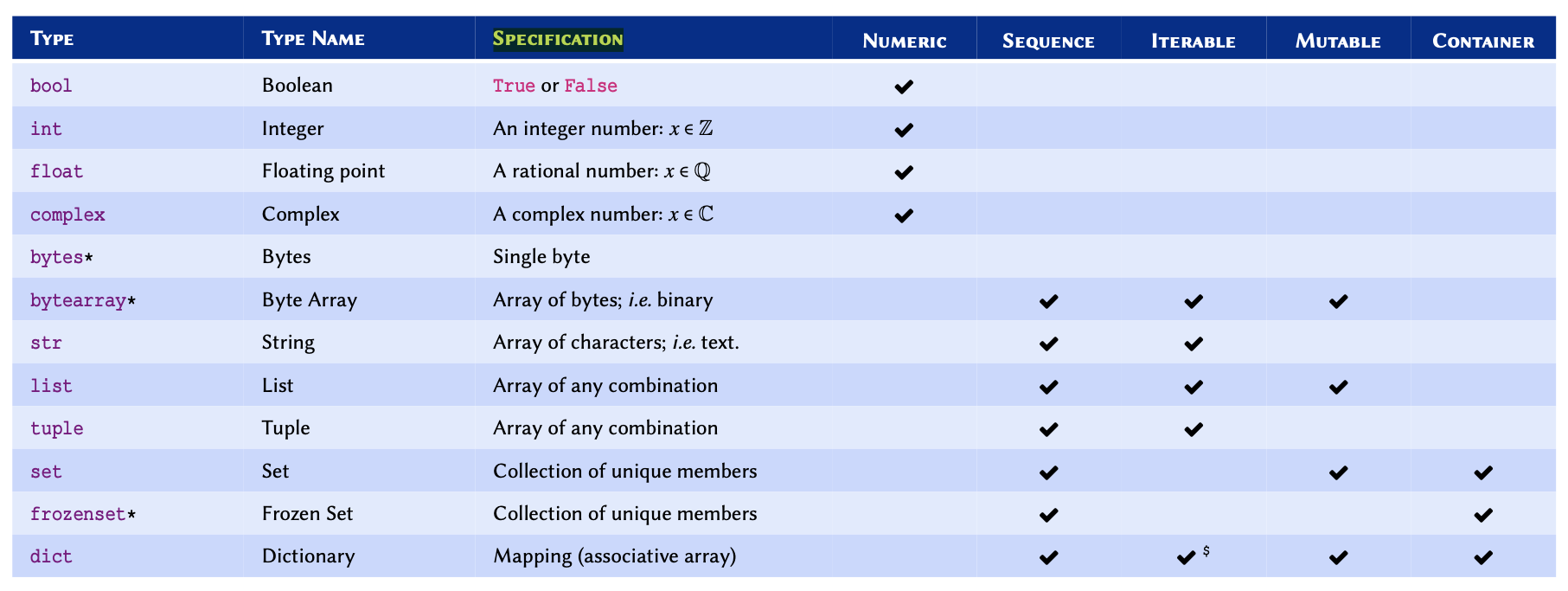

Python enjoys a powerful type system out of the box. The following table - Built-in types in Python - provides a comprehensive reference for the built-in types in Python. Built-in types already exist in the language, and do not require the use or implementation of any third-party libraries.

A comprehensive (but non-exhaustive) reference of built-in (native)

types in Python 3.

A comprehensive (but non-exhaustive) reference of built-in (native)

types in Python 3.

* Not discussed in this course —

included for reference only.

$dict is not

an iterable by default, however, it is possible to iterate through its

keys.

Mutability is an important concept in

programming. A mutable object is an object whose value(s) may be

altered. This will become clearer once we study list and

tuple. Find out more about mutability in Python from the documentation.

Complex numbers refer to a set of

numbers that have both a real component, and an imaginary component;

where the imaginary part is defined as \(\sqrt{-1}\). These numbers are very useful

in the study of oscillatory behaviours and flow (e.g. heat, fluid,

electricity). To learn more about complex numbers, watch this Khan

Academy video tutorial.

Sometimes we might need want to explicitly know what the type of a variable is. To do this, we can use the build-in function type() as follows:

OUTPUT

<class 'int'>OUTPUT

<class 'float'>OUTPUT

<class 'float'>OUTPUT

<class 'complex'>OUTPUT

<class 'str'>Remember

In Python, a variable/value of a certain type may be referred to as an

instance of that type. For instance, an integer value whose

type in Python is defined as int is said to be an

instance of type int.

Practice Exercise 5

Determine and display the type for each of these values:

- 32

- 24.3454

- 2.5 + 1.5

- “RNA Polymerase III”

- 0

- .5 - 1

- 1.3e-5

- 3e5

The result for each value should be represented in the following format:

Value X is an instance of <class 'Y'>

OUTPUT

Value 32 is an instance of <class 'int'>PYTHON

value = 24.3454

value_type = type(value)

print('Value', value, 'is an instance of', value_type)OUTPUT

Value 24.3454 is an instance of <class 'float'>PYTHON

value = 2.5 + 1.5

value_type = type(value)

print('Value', value, 'is an instance of', value_type)OUTPUT

Value 4.0 is an instance of <class 'float'>PYTHON

value = "RNA Polymerase III"

value_type = type(value)

print('Value', value, 'is an instance of', value_type)OUTPUT

Value RNA Polymerase III is an instance of <class 'str'>OUTPUT

Value 0 is an instance of <class 'int'>PYTHON

value = .5 - 1

value_type = type(value)

print('Value', value, 'is an instance of', value_type)OUTPUT

Value -0.5 is an instance of <class 'float'>PYTHON

value = 1.3e-5

value_type = type(value)

print('Value', value, 'is an instance of', value_type)OUTPUT

Value 1.3e-05 is an instance of <class 'float'>OUTPUT

Value 300000.0 is an instance of <class 'float'>Conversion of types

Why convert types?

It is sometimes necessary to have the values returned by the input() function — i.e. the user’s response, in other types. Imagine the following scenario:

“We ask our user to enter the

total volume of their purified protein, so that we can work out the

amount of assay they need to conduct a specific experiment. To calculate

this assay volume using the volume of the purified protein, we need to

perform mathematical calculations based on the response we receive from

our user. It is not possible to perform mathematical operations on

non-numeric values. Therefore, we ought to somehow convert the type from

str to a numeric type.”

The possibility of converting from one type to another depends entirely

on the value, the source type, and the target

type. For instance; we can convert an instance of type

str (source type) to one of type int (target

type) if and only if the source value consists entirely of numbers and

there are no other characters.

Remember

To convert a variable from one type to another, we use the Type Name of the target type (as described in Table Built-in types in Python and treat it as a function.

For instance, to convert a variable to integer, we:

- look up the Type Name for integer from Table Built-in types in Python

- then treat the Type Name as a function:

int() - use the function to convert our variable: new_var =

int(old_var)

Here is an example of how we convert types in Python:

OUTPUT

12 <class 'str'>OUTPUT

12 <class 'int'>If we attempt to convert a variable that contains non-numeric values,

a ValueError is raised:

OUTPUT

12y <class 'str'>OUTPUT

ValueError: invalid literal for int() with base 10: '12y'Practice Exercise 6

In programming, we routinely face errors resulting from different mistakes. The process of finding and correcting such mistakes in the code is referred to as debugging.

We have been given the following piece of code written in Python:

value_a = 3

value_b = '2'

result = value_a + value_b

print(value_a, '+', value_b, '=', result)But when the code is executed, we encounter an error message as follows:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'int' and 'str'Debug the snippet so that the correct result is displayed:

3 + 2 = 5

Handling Input Variables

Discussion

When we use input() to obtain a value from the user, the

results are by default an instance of type str. An

input() function always stores the response as a

str value, no matter what the user enters. However, it is

possible to convert the type afterwards.

Remember

The input() function always returns a value of type

str regardless of the user’s response. In other words, if a

user’s response to an input() request is numeric, Python will

not automatically recognise it as a numeric type.

We may use type conversion in conjunction with the values returned by the input() function:

response = input('Please enter a numeric value: ')

response_numeric = float(response)

print('response:', response)

print('response type:', type(response))

print('response_numeric:', response_numeric)

print('response_numeric type:', type(response_numeric))The output shows the results when we enter numeric values as directed.

Practice Exercise 7

We know that each amino acid in a protein is encoded by a triplet of mRNA nucleotides.

With that in mind, alter the script you wrote for Practice Exercise 3 and use the number of amino acids entered by the user to calculate the number of mRNA nucleotides.

Display the results in the following format:

ENZYME_NAME is an enzyme with AMINO_ACIDS amino acids and NUCLEOTIDES nucleotides.

where NUCLEOTIDES is the total number of mRNA

nucleotides that you calculated.

Note: Multiplication is represented using the

asterisk (*) sign.

enzyme = input('Please enter the name of an enzyme: ')

length = input('How many amino acids does the enzyme contain? ')

nucleotides = 3 * int(length)

print(enzyme, 'is an enzyme with', length, 'amino acids and', nucleotides, 'nucleotides.')Variable scopes

Resolution of namesWhen defining a variable, we should always consider where in our program we intend to use it. The more localised our variables, the better. This is because local variables are easier to distinguish, and thus reduce the chance of making mistakes — e.g. unintentionally redefining or altering the value of an existing variable.

Therefore, the scope of a variable defines the ability to reference a variable from different points in our programs. The concept of local variables becomes clearer once we explore functions in programming in chapter Functions.

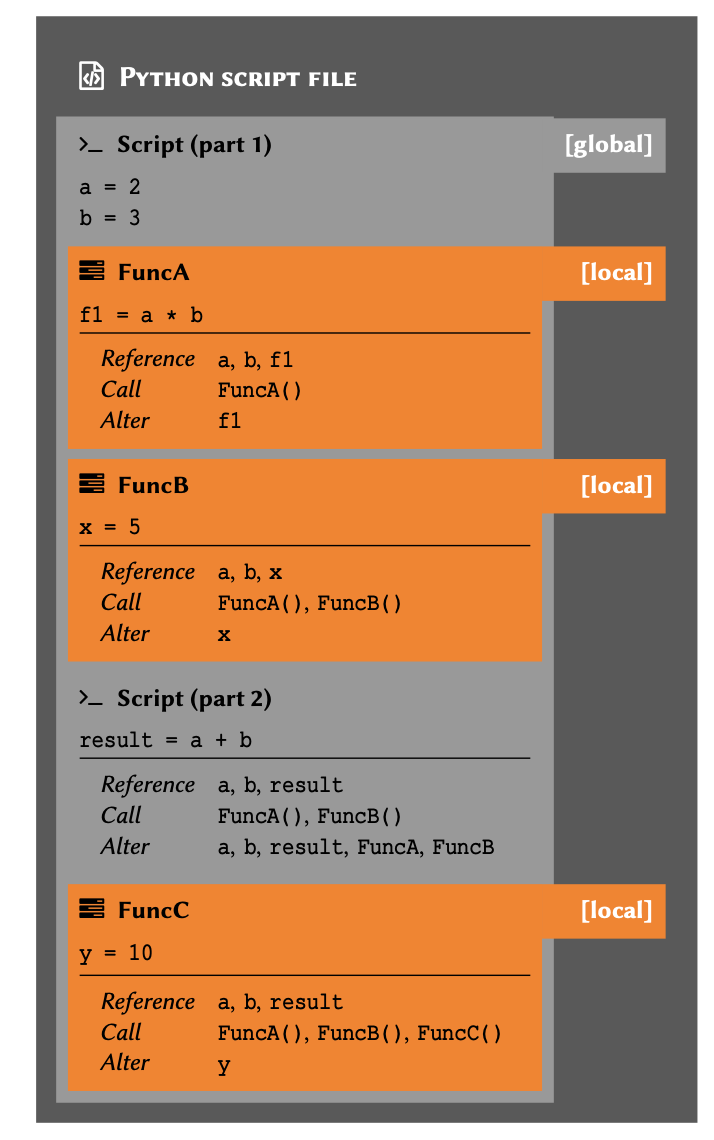

As displayed in Figure Variable scopes, the point at or from which a variable can be referenced depends on the location where the variable is defined.

In essence, there are three general rules to remember in relation to variable scopes in Python:

I. A variable that is defined in the outer scope, can be accessed or called in the inner scopes, but it cannot be altered implicitly. Not that such variables may still be altered using special techniques (not discussed).

- A variable that is defined in the innermost scopes (local), can only be accessed, called, or altered within the boundaries of the scope it is defined in.

- The inner scopes from which a variable is referenced must

themselves be contained within the defining scope — e.g. in

FuncBof Figure Variable scopes, we can referencea,b, andx; but notf1. This is because the scope off1isScript→FuncA, so it can only be referenced fromScript→FuncA→ …, but not `Script→ … orScript→FuncB→ ….

As we discussed earlier in this lesson, it is paramount to remember that

Python is an interpreted language. This means that the Python

interpreter goes through the codes that we write line by line,

interpreting it to machine language. It is only then that the commands

are processed and executed by the computer. On that account, a variable

(or a function) can be referenced only after its initial

definition. That is why, for instance, in Script (part 2)

of Figure Variable scopes, we can

reference every variable and function except for FuncC,

which is declared further down in the code hierarchy.

Although scope and hierarchy appear at first glance as theoretical concepts in programming, their implications are entirely practical. The definition of these principles vary from one programming language to another. As such, it is essential to understand these principles and their implications in relation to any programming language we are trying to learn.

Operations

Through our experimentation with variable types, we already know that variables may be subjected to different operations.

When assessing type conversions, we also established that the operations we can apply to each variable depend on the type of that variable. To that end, we learned that although it is sometimes possible to mix variables from different types to perform an operation (for example multiplying a floating point number with an integer), there are some logical restrictions in place.

Throughout this section, we will take a closer look into different types of operations in Python. This will allow us to gain a deeper insight, and to familiarise ourselves with the underlying logic.

To recapitulate on what we have done so far, we start off by reviewing additions — the most basic of all operations.

Give the variable total_items:

OUTPUT

2We can increment the value of an existing variable by

1 as follows:

OUTPUT

3Given two different variables, each containing a different value; we can perform an operation on these values and store the result in another variable without altering the original variables in any way:

OUTPUT

7We can change the value of an existing variable using a value stored in another variable:

OUTPUT

12There is also a shorthand method for applying this operation on an existing variable:

OUTPUT

2OUTPUT

3OUTPUT

8As highlighted in the introduction, different operations may be applied to any variable or value. We can now explore the most fundamental operations in programming, and learn about their implementation in Python.

Remember

There are 2 very general categories of operations in programming: mathematical, and logical. Naturally, we use mathematical operations to perform calculations, and logical operations to perform tests.

Mathematical Operations

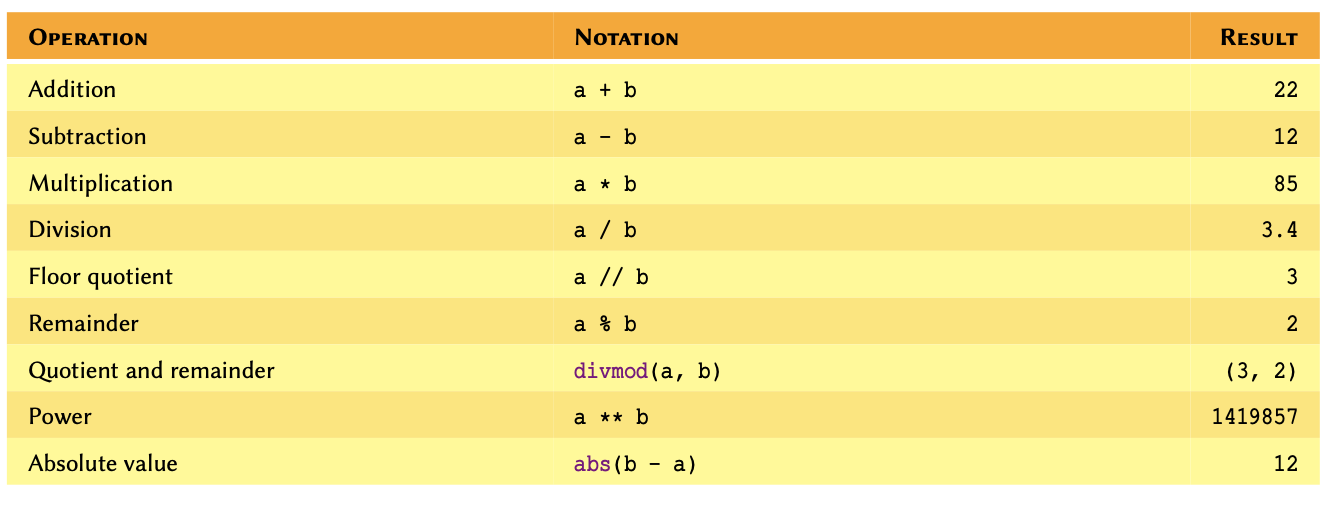

Suppose a and b are two variables

representing integers, as follows:

a = 17

b = 5Using a and b we can itemise built-in

mathematical operations in Python as follows:

Remember

As far as mathematical operations are concerned, variables

a and b may be an instance of any

numeric type. See Table Routine

mathematical operations in Python to find out more about numeric

types in Python.

Values of type int have been chosen in our examples to

facilitate the understanding of the results.

Practice Exercise 8

- Calculate the following and store the results in appropriately named variables:

- \(5.8 \times 3.3\)

- \(\frac{180}{6}\)

- \(35 - 3.0\)

- \(35 - 3\)

- \(2^{1000}\)

Display the result of each calculation – including the type, in the following format:

Result: X is an instance of <class 'Y'>

- Now using the results you obtained:

I. Can you explain why the result of \(35 - 3.0\) is an instance of type

float, whilst that of \(35 - 3\) is of typeint?

II. Unlike the numeric types, string values have a

length. To obtain the length of a string value, we use len().

Convert the result for \(2^{1000}\)

from int to str, then use the aforementioned

function to work out the length of the number — i.e. how many digits is

it made of?

If you feel adventurous, you can try this for \(2^{10000}\) or higher; but beware that you might overwhelm your computer and need a restart it if you go too far (i.e. above \(2^{1000000}\)). Just make sure you save everything beforehand, so you don’t accidentally lose your work.

Hint: We discuss len() in our subsection of arrays arrays lesson. However,

at this point, you should be able to use the official function

documentation to figure out how it works. To access a function’s

documentation or docstring within Jupyter Notebook, for example you can

use help(function_name) to reveal it’s documentation.

Clicking within the function (for example, placing your cursor inside

the function len) and using shift+tab can also

be an easy shortcut for viewing a function’s docstring.

OUTPUT

Result: 19.139999999999997 is an instance of <class 'float'>OUTPUT

Result: 30.0 is an instance of <class 'float'>OUTPUT

Result: 32.0 is an instance of <class 'float'>OUTPUT

Result: 32 is an instance of <class 'int'>OUTPUT

Result: 10715086071862673209484250490600018105614048117055336074437503883703510511249361224931983788156958581275946729175531468251871452856923140435984577574698574803934567774824230985421074605062371141877954182153046474983581941267398767559165543946077062914571196477686542167660429831652624386837205668069376 is an instance of <class 'int'>

In the case of \(35 - 3.0\) vs \(35 - 3\), the former includes a floating

point number. Operations involving multiple numeric types always produce

the results as an instance of the type that covers all of the operands –

i.e. float covers int, but not vice-versa.

Interesting Fact

As of Python 3.6, you can use an underscores (_)

within large numbers as a separator to make them easier to read

in your code. For instance, instead of x = 1000000, you can

write x = 1_000_000.

Shorthand:

When it comes to mathematical operations in Python, there is a frequently used shorthand method that every Python programmer should be familiar with.

Suppose we have a variable defined as total_residues = 52

and want to perform a mathematical operation on it. However, we would

like to store the result of that operation in

total_residues instead of a new variable. We can do this as

follows:

OUTPUT

60OUTPUT

50OUTPUT

100OUTPUT

25.0OUTPUT

12.0OUTPUT

2.0OUTPUT

8.0We can also perform such operations using multiple variables:

PYTHON

total_residues = 52

new_residues = 8

number_of_proteins = 3

total_residues += new_residues

print(total_residues)OUTPUT

60OUTPUT

84Practice Exercise 9

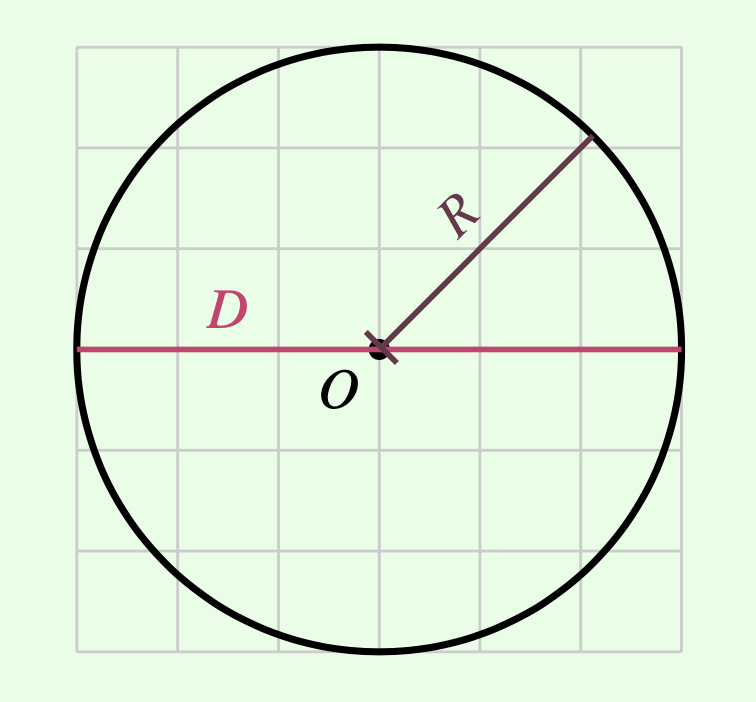

- Given:

- Circumference: \(C = 18.84956\)

- Radius: \(R = 3\)

and considering that the properties of a circle are defined as follows:

\[\pi = \frac{C}{D}\] calculate

\(\pi\) using the above equation and

store it in a variable named pi:

Then round the results to 5 decimal places and display the result in the following format:

The value of pi calculated to 5 decimal places: X.XXXXX

Note: To round floating point numbers in Python, we use the function round(). This is a built-in function that takes two input arguments: the first is the variable/value to be rounded, and the second is the number of decimal places we wish to round to. Read more about the round() function in its official documentation.

-

Now without creating a new variable, perform the following operation:

\[pi = \frac{pi}{(3 \bmod 2) - 1}\]

where the expression ’‘\(3 \bmod 2\)’’ represents the remainder for the division of 3 by 2.

Explain the output.

pi /= (3 % 2) - 1

The calculation raises a ZeroDivisionError. This is

because division by zero is mathematically impossible.

Precedence:

In mathematics and computer programming, there are a series of conventional rules on the precedence of procedures to evaluate a mathematical expression. This collection of rules is referred to as the order of operation or operator precedence.

Suppose we have a mathematical expression as follows:

\[x = 2 + 3 \times 9\]Such an expression can only be evaluated correctly if we do the multiplication first and then perform the addition. This means that the evaluation is done as follows:

\[given:3 \times 9 = 27\] \[\implies x = 2 + 27\] \[ = 29\]

For instance, in an expression such as:

\[x = 2 \times (3 + (5 - 1)^2)\]

the evaluation workflow may be described as follows:

\[x = 2 \times (3 + 4^2)\] \[ = 2 \times (3 + 16)\] \[ = 38\]The same principle applies in Python. This means that if we use Python to evaluate the above expression, the result would be identical:

OUTPUT

38Remember

Operator precedence in mathematical operations may be described as follows:

- Exponents and roots

- Multiplication and division

- Addition and subtraction

If there are any parentheses ( ) in the expression, the

expression is evaluated from the innermost parenthesis, outwards.

Practice Exercise 10

Display the result of each item in the following format:

EXPRESSION = RESULTFor example:

2 + 3 = 5- Calculate each expression without using parentheses:

- \(3 \times \frac{2}{4}\)

- \(5 + 3 \times \frac{2}{4}\)

- \(3 \times \frac{2}{4} + 5\)

- \(\frac{2}{4} \times 3\)

- Calculate these expressions using parentheses:

- \(5 + \frac{2}{4} \times 3\)

- \(5 + \frac{2 \times 3}{4}\)

- \(5 + \frac{2}{4 \times 3}\)

- Given

a = 2

b = 5use a and b to calculate the following

expressions:

- \((a + b)^2\)

- \(a^2 + 2ab + b^2\)

OUTPUT

3 * 2 / 4 = 1.5OUTPUT

5 + 3 * 2 / 4 = 6.5OUTPUT

3 * 2 / 4 + 5 = 6.5OUTPUT

2 / 4 * 3 = 1.5Non-numeric values

It sometimes makes sense to apply some mathematical operations to non-numeric variables, too.

We can multiply strings in order to repeat them. There is no specific advantage to using multiplication instead of manually repeating characters or words, but it does make our code look cleaner, which is ideal.

We can also add string values to each other. This is called string concatenation. It is a useful method for concatenating, and provides a useful method for combining multiple strings and/or string variables.

PYTHON

SEPARATOR = '-' * 20

NEW_LINE = '\n'

SPACE = ' '

forename = 'Jane'

surname = 'Doe'

birthday = '01/01/1990'

full_name = forename + SPACE + surname

data = full_name + NEW_LINE + SEPARATOR + NEW_LINE + 'DoB: ' + birthday

print(data)OUTPUT

Jane Doe

--------------------

DoB: 01/01/1990Remember

New line character or '\n' is a universal directive to

induce a line-break in Unix-based operating systems (Mac OS) and Linux).

In WINDOWS, we usually us '\r' or '\r\n'

instead. These are known as escape sequences.

Practice Exercise 11

Symptomatic Huntington’s disease appears to increase in proportion to

the number of CAG trinucleotide repeats (the codon for

glutamine); once these exceed 35 repeats near the beginning of the

Huntingtin (IT15) gene, the individual is phenotypic for

the disease. These CAG repeats are also referred to as a

polyglutamine or polyQ tract.

glutamine_codon = 'CAG'- Create a polynucleotide chain representing 36 glutamine codons.

Store the result in a variable called

polyq_codons.

Display the result as:

Polyglutamine codons with 36 repeats: XXXXXXXXX...- Use len() to work out the length of

polyq_codons, and store the result in a variable calledpolyq_codons_length.

Display the result in the following format:

Number of nucleotides in a polyglutamine with 36 repeats: XXXUse len() to work out the length of

glutamine_codon, and store the result in variableamino_acids_per_codon.Divide

polyq_codons_lengthbyamino_acids_per_codonto verify that the chain contains the total codons to encode exactly 36 amino acids. Store the result in a variable titledpolyq_peptide_length.

Display the result in the following format:

Number of amino acids in a polyglutamine with 36 repeats: XXX- Determine the types for the following variable:

amino_acids_per_codon

polyq_codons_length

-

polyq_peptide_length

and display the result for each item in the following format:

Value: XXX - Type: <class 'XXXX'>Are all the variables in task #5 of the same type? Why?

Repeat from task #4, but this time use an alternative method of division as outlined in See Table Routine mathematical operations in Python.

PYTHON

print('Value:', amino_acids_per_codon, '- Type:', type(amino_acids_per_codon))

print('Value:', polyq_codons_length, '- Type:', type(polyq_codons_length))

print('Value:', polyq_peptide_length, '- Type:', type(polyq_peptide_length))OUTPUT

Value: 3 - Type: <class 'int'>

Value: 108 - Type: <class 'int'>

Value: 36.0 - Type: <class 'float'>

No, polyq_peptide_length is an instance of type

float. This is because we used the normal division

(/) and not floor division (//}) to calculate

its value. The result of normal division is always presented as a

floating point number.

PYTHON

polyq_peptide_length = polyq_codons_length // amino_acids_per_codon

print('Number of amino acids in a polyglutamine with 36 repeats:', polyq_peptide_length)

print('Value:', amino_acids_per_codon, '- Type:', type(amino_acids_per_codon))

print('Value:', polyq_codons_length, '- Type:', type(polyq_codons_length))

print('Value:', polyq_peptide_length, '- Type:', type(polyq_peptide_length))OUTPUT

Number of amino acids in a polyglutamine with 36 repeats: 36

Value: 3 - Type: <class 'int'>

Value: 108 - Type: <class 'int'>

Value: 36 - Type: <class 'int'>Interesting Fact

The Boolean data type is named after the English mathematician and logician George Boole (1815–1864).

Logical Operations

An operation may sometimes involve a comparison. The result of these

operations may be either True or False. This

is known as the Boolean or bool data type. In

reality, however, computers record True and

False as 1 and 0, respectively.

Operations with Boolean results are referred to as logical operations. Testing the results of such operations is referred to as truth value testing.

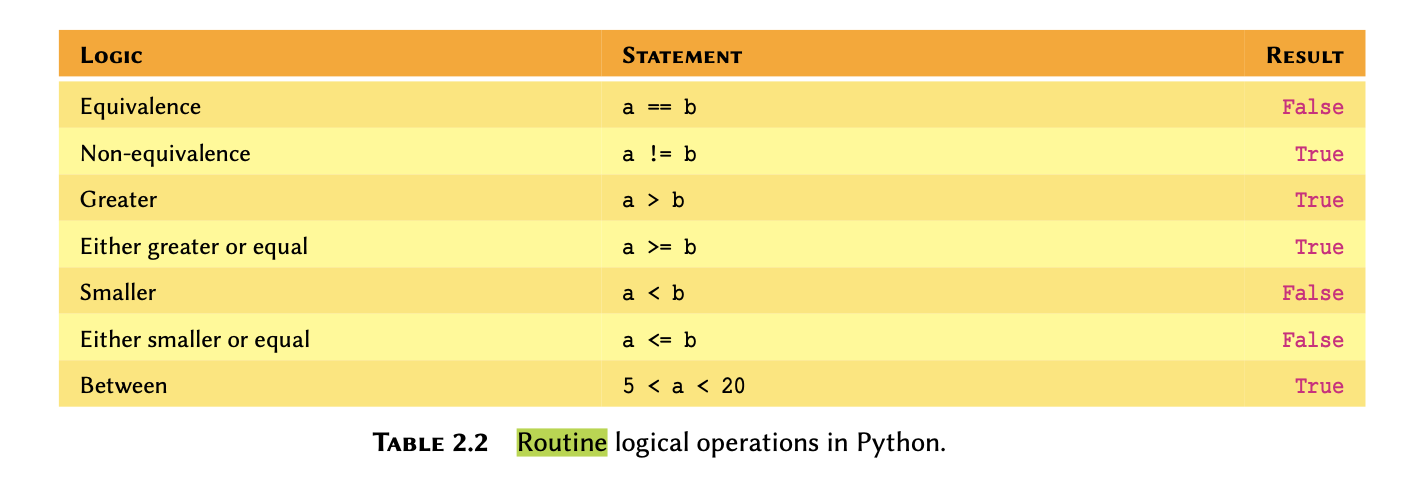

Given the two variables a and b as

follows:

a = 17

b = 5Boolean operations may be defined as outlined in this Table Routine logical operations in Python..

Practice Exercise 12

We know that in algebra, the first identity (square of a binomial) is:

\[(a + b)^2 = a^2 + 2ab + b^2\] now given:

a = 15

b = 4- Calculate

\[y_1 = (a + b)^{2}\] \[y_2 = a^2 + 2ab + b^2\]

Display the results in the following format:

y1 = XX

y2 = XX

- Determine whether or not

y_1is indeed equal toy_2. Store the result of your test in another variable calledequivalence. Display the results in the following format:

Where a = XX and b = XX:

y1 is equal to y2: [True/False]Negation

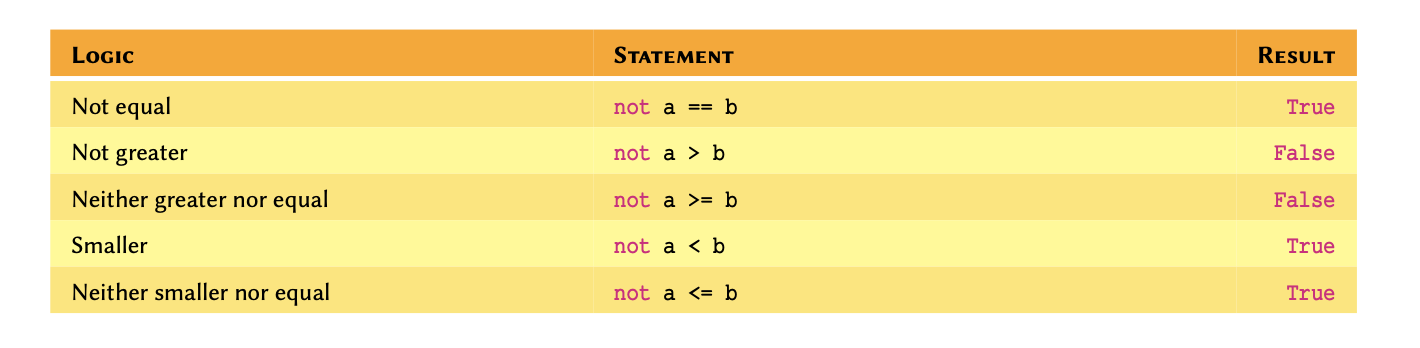

We can also use negation in logical operations. Negation in Python is implemented using not:

Practice Exercise 13

Using the information from previous Practice Exercise 12:

- Without using not, determine whether or not

y_1is not equal toy_2. Display the result of your test and store it in another variable calledinequivalent.

- Negate

inequivalentand display the result.

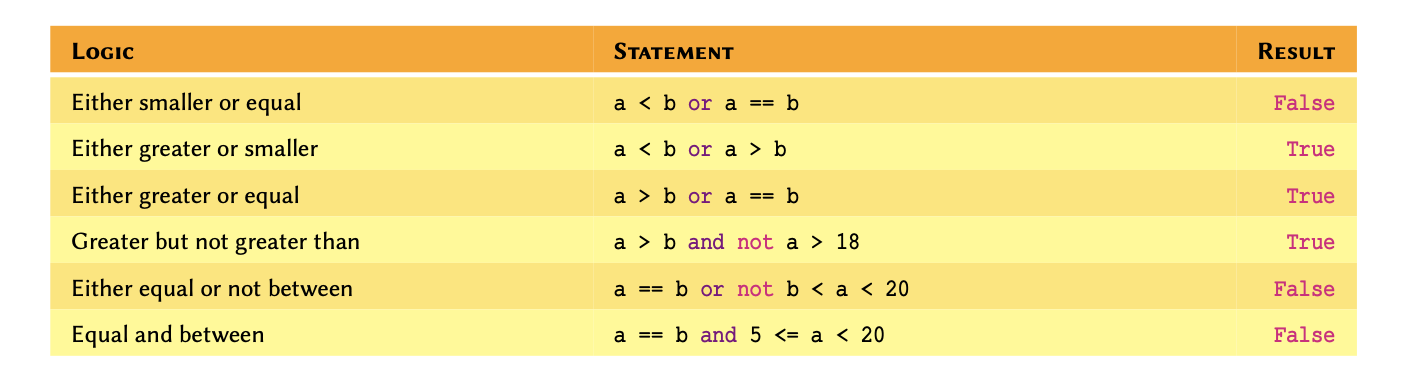

Disjunctions and Conjunctions:

Logical operations may be combined using conjunction with and and disjunction with or to create more complex logics:

Practice Exercise 14

Given

a = True

b = False

c = TrueEvaluate the following statements:

- a == b

- a == c

- a

orb - a

andb - a

orbandc - (a

orb)andc -

notaor(bandc) -

notaornot(bandc) -

notaandnot(bandc) -

notaandnot(borc)

Display the results in the following format:

1. [True/False]

2. [True/False]

...Given that:

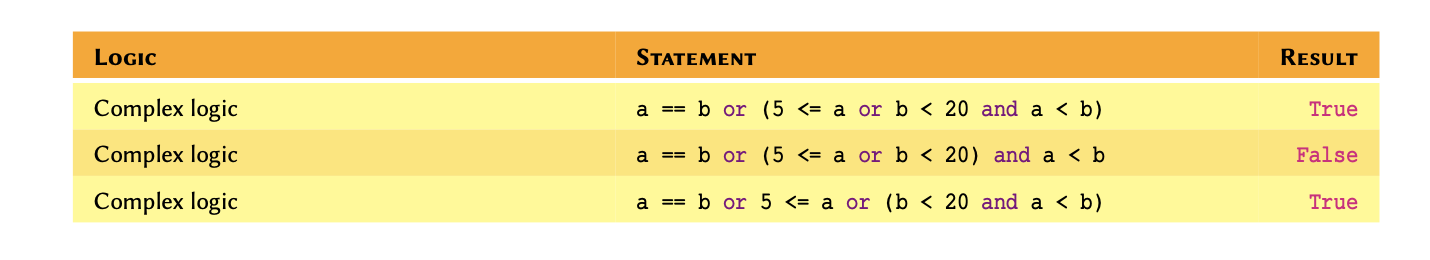

Complex logical operations:

It may help to break down more complex operations, or use parentheses to make them easier to read and write:

Notice that in the last example, all notations is essentially the same, and only varies in terms of the collective results as defined using parentheses. Always remember that in a logical statement:

Logical statement

OUTPUT

TrueOUTPUT

TrueOUTPUT

TrueOUTPUT

FalseOUTPUT

TrueOUTPUT

FalseOUTPUT

TruePYTHON

# Disjunction and negated conjunction and conjunction:

# true AND NOT false AND false

a < b or not b < c and b > aOUTPUT

FalsePYTHON

# Disjunction and negated conjunction - similar to the

# previous example: true AND NOT (false AND false)

a < b or not (b < c and b > a)OUTPUT

TrueThese are only a few examples. There are endless possibilities, try them yourself and see how they work.

Remember

Some logical operations may be written in different ways. However, we should always use the notation that is most coherent in the context of our code. If in doubt, use the simplest or shortest notation.

To that end, you may want to use variables to break complex statements down into smaller fragments:

PYTHON

age_a, age_b = 15, 35

are_positive = age_a > 0 and age_b > 0

a_is_older = are_positive and (age_a > age_b)

b_is_older = are_positive and (age_a < age_b)

a_is_teenager = are_positive and 12 < age_a < 20

b_is_teenager = are_positive and 12 < age_b < 20

a_is_teenager and b_is_olderOUTPUT

TrueOUTPUT

FalseOUTPUT

TruePractice Exercise 15

Given

a = 3

b = 13Test the following statements and display the results:

- \(a^2 < b\)

- \(3 - a^3 < b\)

- \(|25 - a^2| > b\)

- \(25 \bmod a^2 > b\)

- \(25 \bmod a^2 > b\) or \(25 \bmod b < a\)

- \(25 \bmod a^2 < b\) and \(25 \bmod b > a\)

- \(\frac{12}{a}\) and \(a\times4 < b\)

where “|…|” represents the absolute value, and “\(n \bmod m\)” represents the remainder for the division of \(n\) by \(m\).}

Display the results in the following format:

1. [True/False]

2. [True/False]

...Exercises

End of chapter Exercises

Write and execute a Python code to display your own name as an output in the Terminal.

Write and execute a Python code that:

- Displays the text:

Please press enter to continue..., and waits for the user to press enter. - Once the user presses enter, the program should display

Welcome to my programme!before terminating.

-

We have an enzyme whose reaction velocity is \(v=50~mol \cdot L^{-1} \cdot s^{-1}\) at the substrate concentration of \([S] = K_{m} = 2.5~mol \cdot L^{-1}\). Work out the maximum reaction velocity or \(V_{\max}\) for this enzyme using the Michaelis-Menten equation:

\[v = \frac{V_{\max} [\textrm{S}]}{K_{m} + [\textrm{S}]}\]

Key Points

- Two key functions for I/O operations are print() and input()

- Three most commonly used variables such as

int,float, andstr. - Variable scope can be local or global depending where they are being used.

- Mathematical operations follow conventional rules of precedence

- Logical operations provide results in Boolean (True or False)