Introduction to Arrays

Last updated on 2024-08-05 | Edit this page

Download Chapter notebook (ipynb)

Mandatory Lesson Feedback Survey

Overview

Questions

- What are the different types of arrays?

- How is data stored and retrieved from an array?

- What are nested arrays?

- What are tuples?

Objectives

- Understanding difference between lists and tuples.

- Understanding operations on arrays.

- Storing multidimensional data.

- Understanding the concepts of mutability and immutability.

Prerequisite

So far, we have been using variables to store individual values. In some circumstances, we may need to access multiple values in order to perform operations. On such occasions, defining a variable for every single value can become very tedious. To address this, we use arrays.

Arrays are variables that hold any number of values. Python provides

three types of built-in arrays. These are: list,

tuple, and set. There are a several common

features among all arrays in Python; however, each type of array enjoys

its own range of unique features that facilitates specific operations.

Remember

Each item inside an array may be referred to as an item or a member of that array.

Lists

Lists are the most frequently-used type of arrays in Python. It is therefore important to understand how they work, and how can we use them, and the features they offer, to our advantage.

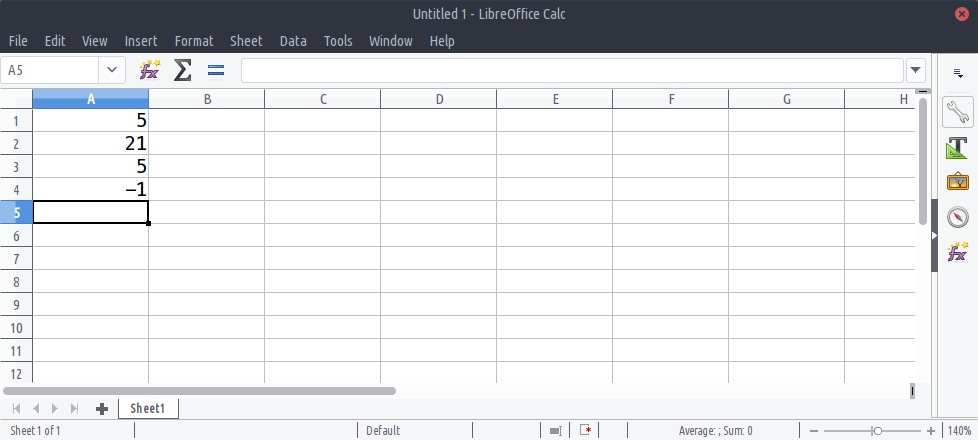

The easiest way to imagine how a list works, is to think of

it as a table that can have any number of rows. This is akin to a

spreadsheet with one column. For instance, suppose we have a table with

four rows in a spreadsheet application, as follows:

The number of rows in an array determines its length. The above table has four rows; therefore it is said to have a length of 4.

Implementation

Remember

In order to implement a list in Python, we place values

into this list and separate them from one another using commas inside

square brackets: list = [1,2,3].

OUTPUT

[5, 21, 5, -1]OUTPUT

<class 'list'>Practice Exercise 1

Implement a list array called fibonacci, whose members

represent the first 8 numbers of the Fibonacci

sequence as follows:

| FIBONACCI NUMBERS (FIRST 8) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 13 | 21 |

Indexing

In an array, an index is an integer (whole number) that corresponds to a specific item in that array.

You can think of an index as a unique reference or key that corresponds to a specific row in a table. We don’t always write the row number when we create a table. However, we always know that the third row of a table refers to us starting from the first row (row #1), counting three rows down and there we find the third row.

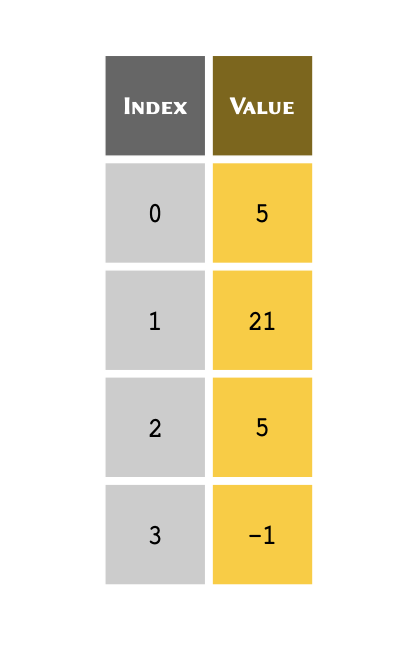

Python, however, uses what we term zero-based indexing. We don’t count the first row as row #1; instead, we consider it to be row #0. As a consequence of starting from #0, we count rows in our table down to row #2 instead of #3 to find the third row. So our table may,essentially, be visualised as follows:

Remember

Python uses zero-based indexing system. This means that the first row of an array, regardless of its type, is always referred to with index #0.

With that in mind, we can use the index for each item in the list, in

order to retrieve it from a list.

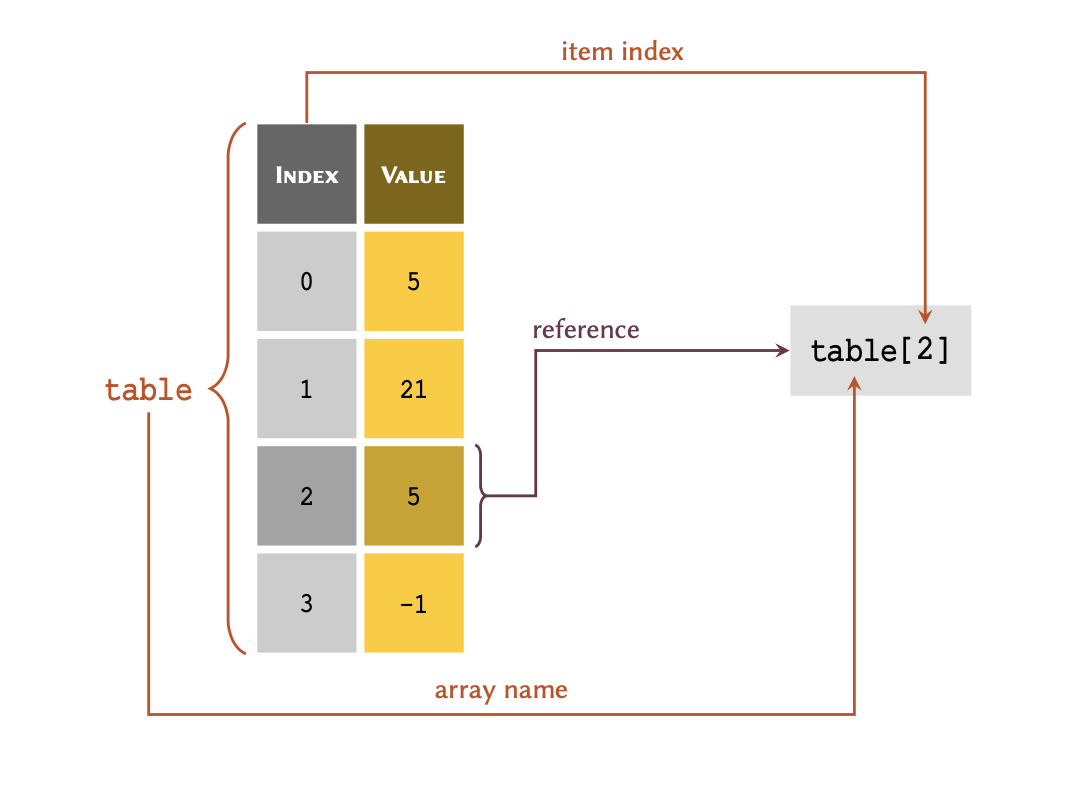

Given the following list of four members stored in a

variable called table:

table = [5, 21, 5, -1]

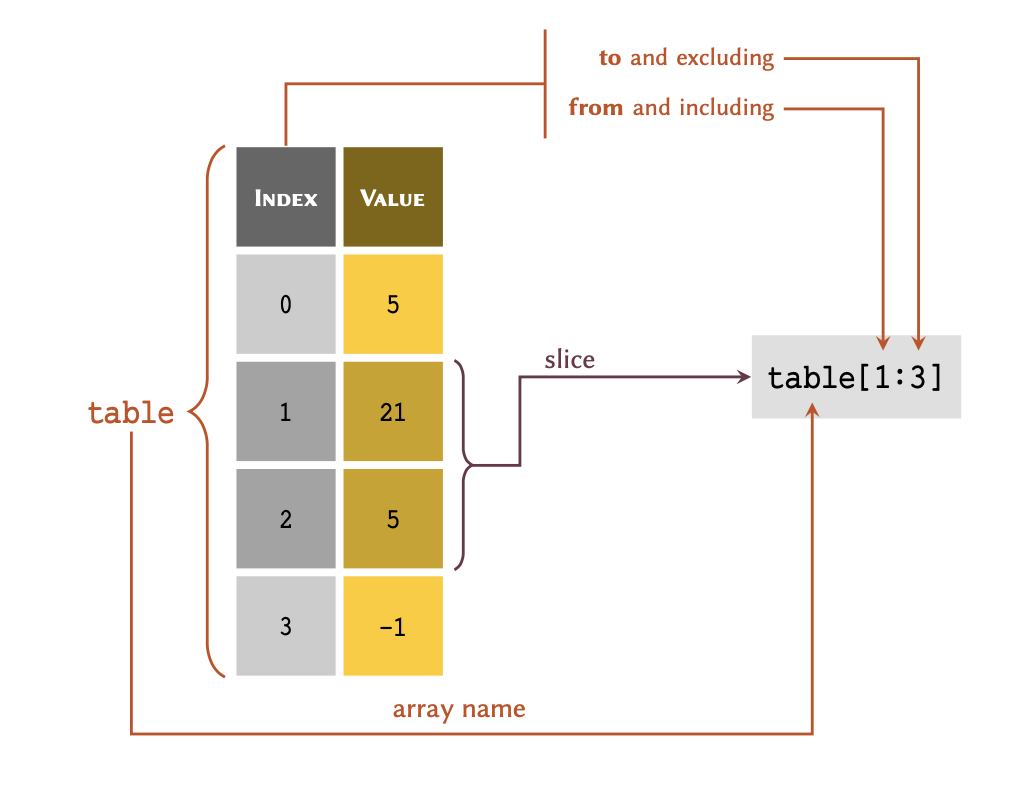

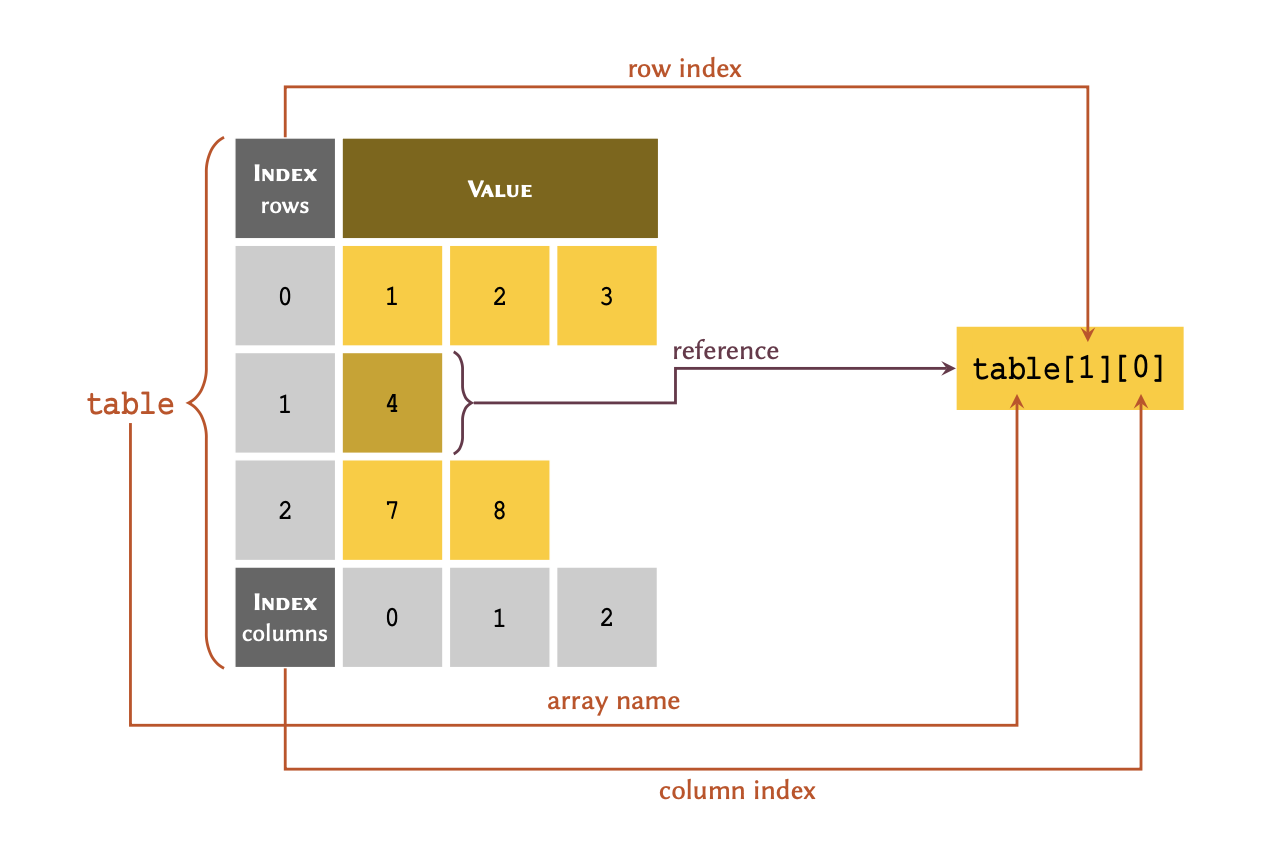

As illustrated in this figure; in order to retrieve a member of an array through its index, we write the name of the variable immediately followed by the index value inside a pair of square brackets — e.g. table[2]. Note, you may have noticed our interchangeable use of the terms ‘list’ and ‘array’. That is because a list, in Python, can be considered as a type of dynamic array (they can increase or decrease in size, as required).

OUTPUT

5OUTPUT

5OUTPUT

-1Practice Exercise 2

Retrieve and display the 5th Fibonacci number from the

list you created in the previous Practice Exercise 1.

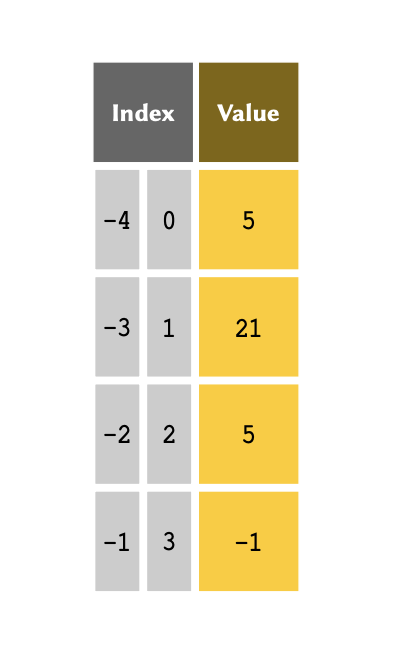

It is sometimes more convenient to index an array, backwards — that is, to reference the members from the bottom of the array, first. This is termed negative indexing, and is particularly useful when we are dealing with lengthy arrays. The indexing system in Python support both positive and negative indexing systems.

The table above therefore may also be represented, as follows:

Remember

Unlike the normal indexing system, which starts from #0, negative indexes start from #-1. This serves to definitely highlight which indexing system is being used.

If the index is a negative number, the indices are counted from the

end of the list. We can implement negative indices in the

same way as positive indices:

OUTPUT

-1OUTPUT

5OUTPUT

21We know that in table, index #-3 refers the same value as index #1. So let us go ahead and test this:

OUTPUT

TrueIf the index requested is larger than the length of the

list minus one, an IndexError will be

raised:

OUTPUT

IndexError: list index out of rangeRemember

The values stored in a list may be referred to as the

members of that list.

Practice Exercise 3

Retrieve and display the last Fibonacci number from the

list you created in Practice Exercise 1.

Slicing

It is also possible that you may wish to retrieve more than one value

from a list at a time, as long as the values are in

consecutive rows. This process is is termed , and may be

visualised, as follows:

Remember

Python is a non-inclusive language. This means that in table[a:b], a slice includes all the values from, and including index a right down to, but excluding, index b.

Given a list representing the above table:

table = [5, 21, 5, -1]we may retrieve a slice of table, as follows:

OUTPUT

[21, 5]print(table[0:2])If the first index of a slice is #0, the slice may also be written as:

OUTPUT

[5, 21]Negative slicing is also possible:

PYTHON

# Retrieves every item from the first member down

# to, but excluding the last one:

print(table[:-1])OUTPUT

[5, 21, 5]OUTPUT

[21]If the second index of a slice represents the last index of a

list, it would be written as:

OUTPUT

[5, -1]OUTPUT

[21, 5, -1]We may also store indices and slices in variables:

OUTPUT

[21, 5]The slice() function may also be used to create a slice variable:

OUTPUT

[21, 5]Practice Exercise 4

Retrieve and display a slice of Fibonacci numbers from the

list you created in Practice Exercise 1 that includes

all the members from the second number onwards — i.e. the slice

must not include the first value in the list.

Note

Methods are features of Object-Oriented

Programming (OOP) - a programming paradigm that we do not discuss in

the context of this course. You can think of a method as a

function that is associated with a specific type. The

job of a method is to provide a certain functionality unique to

the type it is associated with. In this case,

.index() is a method of type list

that, given a value, finds and produces its index from the

list.

From value to index

Given a list entitled table as:

we can also determine the index of a specific value. To do so, we use the .index() method:

OUTPUT

1OUTPUT

3If a value is repeated more than once in the list, the

index corresponding to the first instance of that value is

returned:

OUTPUT

0If a value does not exist in the list, using

.index() will raise a ValueError:

OUTPUT

ValueError: 9 is not in listPractice Exercise 5

Find and display the index of these values from the list

of Fibonacci numbers that you created in Practice Exercise 1:

- 1

- 5

- 21

Mutability

Mutability is a term that we use to refer to a structure’s capability of

being change, once it is created. Arrays of type list are

modifiable. That is, we can add new values, change the existing

ones or remove them from the array, altogether. Variable types that

allow their contents to be modified are referred to as mutable

types in programming.

Addition of new members

Given a list called table, we can add new values to

it using .append():

OUTPUT

[5, 21, 5, -1, 29]OUTPUT

[5, 21, 5, -1, 29, 'a text']

Sometimes, it may be necessary to insert a value at a specific position

or index in a list. To do so, we may use

.insert(), which takes two input arguments; the first

representing the index, and the second the value to be inserted:

OUTPUT

[5, 21, 5, 56, -1, 29, 'a text']Practice Exercise 6

Given fibonacci - the

list representing the first 8 numbers in the Fibonacci

sequence that you created in Practice Exercise 1:

The 10th number in the Fibonacci sequence is 55. Add this value to fibonacci.

Now that you have added 55 to the

list, it no longer provides a correct representation of the Fibonacci sequence. Alter fibonacci and insert the missing number such that the list correctly represents the first 10 numbers in the Fibonacci sequence, as follows:

| FIBONACCI NUMBERS (FIRST 8) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 13 | 21 | 34 | 55 |

Modification of members

Given a list as:

we can also modify the exiting value or values inside a

list. This process is sometimes referred to as item

assignment:

OUTPUT

[5, 174, 5, 56, -1, 29, 'a text']OUTPUT

[5, 174, 5, 19, -1, 29, 'a text']It is also possible to perform item assignment over a slice containing any number of values. Note that when modifying a slice, the replacement values must be the same length as the slice we are trying to replace:

PYTHON

print('Before:', table)

replacement = [-38, 0]

print('Replacement length:', len(replacement))

print('Replacement length:', len(table[2:4]))

# The replacement process:

table[2:4] = replacement

print('After:', table)OUTPUT

Before: [5, 174, 5, 19, -1, 29, 'a text']

Replacement length: 2

Replacement length: 2

After: [5, 174, -38, 0, -1, 29, 'a text']OUTPUT

[5, 174, 12, 0, -1, 29, 'a text']Practice Exercise 7

Create a list containing the first 10 prime numbers

as:

primes = [2, 3, 5, 11, 7, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29]

Values 11 and 7, however, have been misplaced in the sequence. Correct the order by replacing the slice of primes that represents [11, 7] with [7, 11].

Removal of members

When removing a value from a list, we have two options

depending on our needs: we either remove the member and retain the value

in another variable, or we remove it and dispose of the value,

completely.

To remove a value from a list without retaining it, we use

.remove(). The method takes one input argument, which is the

value we would like to remove from our list:

OUTPUT

[5, 12, 0, -1, 29, 'a text']Alternatively, we can use del; a Python syntax that we can use, in this context, to delete a specific member using its index:

OUTPUT

[5, 12, 0, -1, 29]As established above, we can also delete a member and retain its value. Of course we can do so by holding the value inside another variable before deleting it.

Whilst this is a valid approach, Python’s list provide us

with .pop() to simplify the process even further. The method

takes one input argument for the index of the member to be removed. It

removes the member from the list and returns its value, so

that we can retain it in a variable:

OUTPUT

Removed value: 0

[5, 12, -1, 29]Practice Exercise 8

We know that the nucleotides of DNA include Adenosine, Cytosine, Threonine and Glutamine: A, C, T, and G.

Given a list representing a nucleotide sequence:

strand = ['A', 'C', 'G', 'G', 'C', 'M', 'T', 'A']Find the index of the invalid nucleotide in strand.

Use the index you found to remove the invalid nucleotide from strand and retain the value in another variable. Display the result as:

Removed from the strand: X

New strand: [X, X, X, ...]- What do you think happens once we run the following code, and why? What would be the final result displayed on the screen?

strand.remove('G')

print(strand)One of the two G nucleotides, the one at index 2 of the original array, is removed. This means that the .remove() method removes only first instance of a member in an array. The output would therefore be:

['A', 'C', 'G', 'C', 'M', 'T', 'A']Method–mediated operations

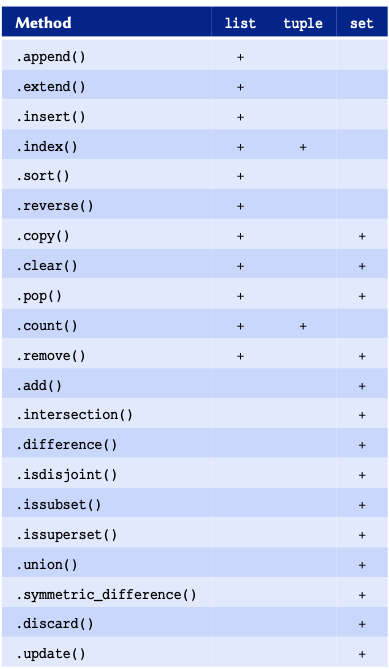

We already know that methods are akin to functions that are associated with a specific type. In this subsection, we will be looking at how operations are performed using methods. We will not be introducing anything new, but will recapitulate what we already know from, but from different perspectives.

So far in this chapter, we have learned how to perform different

operations on list arrays in Python. You may have noticed

that some operations return a result that we can store in a variable,

while others change the original value.

With that in mind, we can divide operations performed using methods into two general categories:

- Operations that return a result without changing the original array:

OUTPUT

2

[1, 2, 3, 4]- Operations that use specific methods to change the original array, but do not necessarily return anything (in-place operations):

OUTPUT

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5]If we attempt to store the output of an operation that does not a

return result, and store this into a variable, the variable will be

created, but its value will be set to None, by default:

OUTPUT

None

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]It is important to know the difference between these types of operations. So as a rule of thumb, when we use methods to perform an operation, we can only change the original value if it is an instance of a mutable type. See Table to find out which of Python’s built-in types are mutable.

The methods that are associated with immutable objects always return the results and do not provide the ability to alter the original value:

- In-place operation on a mutable object of type

list:

OUTPUT

[5, 7]- In-place operation on an immutable object of type

str:

OUTPUT

AttributeError: 'str' object has no attribute 'remove'OUTPUT

567- Normal operation on a mutable object of type

list:

OUTPUT

1- Normal operation on a mutable object of type

list:

OUTPUT

1List members

A list is a collection of members that are independent of

each other. Each member has its own type, and is therefore subject

to the properties and limitations of that type:

OUTPUT

<class 'int'>

<class 'float'>

<class 'str'>

For instance, mathematical operations may be considered a feature of all

numeric types demonstrated in Table. However, unless

in specific circumstance described in subsection Non-numeric

values, such operations do not apply to instance of type

str.

OUTPUT

[2, 2.1, 'abcdef']

A list in Python plays the role of a container that may

incorporate any number of values. Thus far, we have learned how

to handle individual members of a list. In this subsection,

we will be looking at several techniques that help us address different

circumstances where we look at a list from a ‘wholist’

perspective; that is, a container whose members are unknown to us.

Membership test

Membership test operations [advanced]

We can check to see whether or not a specific value is a member of a

list using the operator syntax in:

OUTPUT

TrueOUTPUT

FalseThe results may be stored in a variable:

OUTPUT

TrueSimilar to any other logical expression, we can negate membership tests by using :

OUTPUT

TrueOUTPUT

FalseFor numeric values, int and float

may be used interchangeably:

OUTPUT

TrueOUTPUT

TrueSimilar to other logical expression, membership tests may be incorporated into conditional statements:

OUTPUT

Hello JohnPractice Exercise 9

Given a list of randomly generated peptide sequences

as:

PYTHON

peptides = [

'FAEKE', 'DMSGG', 'CMGFT', 'HVEFW', 'DCYFH', 'RDFDM', 'RTYRA',

'PVTEQ', 'WITFR', 'SWANQ', 'PFELC', 'KSANR', 'EQKVL', 'SYALD',

'FPNCF', 'SCDYK', 'MFRST', 'KFMII', 'NFYQC', 'LVKVR', 'PQKTF',

'LTWFQ', 'EFAYE', 'GPCCQ', 'VFDYF', 'RYSAY', 'CCTCG', 'ECFMY',

'CPNLY', 'CSMFW', 'NNVSR', 'SLNKF', 'CGRHC', 'LCQCS', 'AVERE',

'MDKHQ', 'YHKTQ', 'HVRWD', 'YNFQW', 'MGCLY', 'CQCCL', 'ACQCL'

]Determine whether or not each of the following sequences exist in peptides; and if so, what is their corresponding index:

- IVADH

- CMGFT

- DKAKL

- THGYP

- NNVSR

Display the results in the following format:

Sequence XXXXX was found at index XXLength

Built-in functions: len

The number of members contained within a list defines its

length. Similar to the length of str values as discussed in

mathematical operations Practice Exercise 8 and Practice Exercise

11, we use the built-in function len() also to determine

the length of a list:

OUTPUT

5OUTPUT

3

The len() function always returns an integer value

(int) equal to, or greater than, zero. We can store the

length in a variable and use it in different mathematical or logical

operations:

PYTHON

table = [1, 2, 3, 4]

items_length = len(items)

table_length = len(table)

print(items_length + table_length)OUTPUT

9OUTPUT

TrueWe can also use the length of an array in conditional statements:

PYTHON

students = ['Julia', 'John', 'Jane', 'Jack']

present = ['Julia', 'John', 'Jane', 'Jack', 'Janet']

if len(present) == len(students):

print('All the students are here.')

else:

print('One or more students are not here yet.')OUTPUT

One or more students are not here yet.Remember

Both in and len() may be used in reference to any type of array or sequence in Python.

See Table to find out which of Python’s built-in types are regarded as a sequence.

Practice Exercise 10

Given the list of random peptides defined in Practice Exercise 9:

- Define a

listcalled overlaps, containing the sequences whose presence in peptides you previously confirmed in Practice Exercise 9. - Determine the length of peptides.

- Determine the length of overlaps.

Display yours results as follows:

overlaps = ['XXXXX', 'XXXXX', ...]

Length of peptides: XX

Length of overlaps: XXPYTHON

overlaps = list()

sequence = "IVADH"

if sequence in peptides:

overlaps.append(sequence)

sequence = "CMGFT"

if sequence in peptides:

overlaps.append(sequence)

sequence = "DKAKL"

if sequence in peptides:

overlaps.append(sequence)

sequence = "THGYP"

if sequence in peptides:

overlaps.append(sequence)

sequence = "NNVSR"

if sequence in peptides:

overlaps.append(sequence)

print('overlaps:', overlaps)OUTPUT

overlaps: ['CMGFT', 'NNVSR']Weak References and Copies

In our discussion on mutability, we also explored some

of the in-place operations such as .remove() and

.append(), that we can use to modify an existing

list. The use of these operations gives rise the following

question: What if we need to perform an in-place operation, but also

want to preserve the original array?

In such cases, we create a deep copy of the original array before we call the method and perform the operation.

Suppose we have:

A weak reference for table_a, also referred to as an alias or a symbolic link, may be defined as follows:

OUTPUT

[1, 2, 3, 4] [1, 2, 3, 4]Now if we perform an in-place operation on only one of the two variables (the original or the alias) as follows:

we will effectively change both of them:

OUTPUT

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5] [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]This is useful if we need to change the name of a variable under certain conditions to make our code more explicit and legible; however, it does nothing to preserve an actual copy of the original data.

To retain a copy of the original array, however, we must perform a deep copy as follows:

OUTPUT

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5] [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]where table_c represents a deep copy of table_b.

In this instance, performing an in-place operation on one variable would not have any impacts on the other:

OUTPUT

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]where both the original array and its weak reference (table_a and table_b) changed without influencing the deep copy (table_c).

There is also a shorthand for the .copy() method to create

a deep copy. As far as arrays of type list are

concerned, writing:

new_table = original_table[:]is exactly the same as writing:

new_table = original_table.copy()Here is an example:

PYTHON

table_a = ['a', 3, 'b']

table_b = table_a

table_c = table_a.copy()

table_d = table_a[:]

table_a[1] = 5

print(table_a, table_b, table_c, table_d)OUTPUT

['a', 5, 'b'] ['a', 5, 'b'] ['a', 3, 'b'] ['a', 3, 'b']Whilst both the original array and its weak reference (table_a and table_b) changed in this example; the deep copies (table_c and table_d) have remained unchanged.

Practice Exercise 11

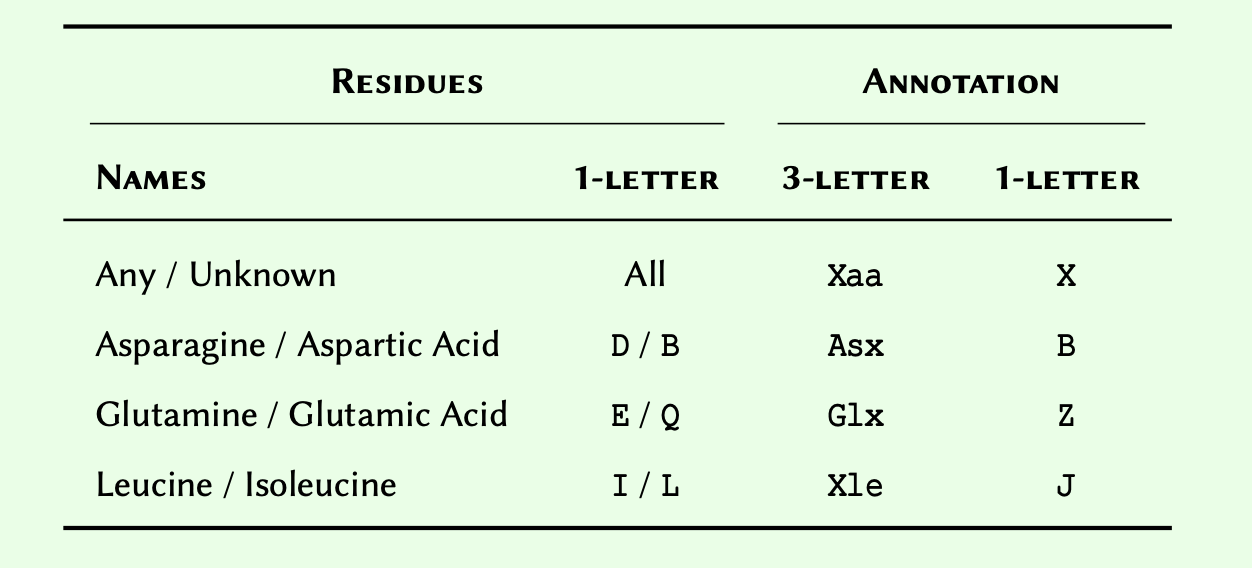

When defining a consensus sequence, it is common to include annotations to represent ambiguous amino acids. Four such annotations are as follows:

Given a list of amino acids as:

PYTHON

amino_acids = [

'A', 'R', 'N', 'D', 'C', 'E', 'Q', 'G', 'H', 'I',

'L', 'K', 'M', 'F', 'P', 'S', 'T', 'W', 'Y', 'V'

]

- Use amino_acids to

create an independent

listcalled amino_acids_annotations that contains all the standard amino acids.

- Add to amino_acids_annotations the 1-letter annotations for the ambiguous amino acids, as outlined in the table.

- Evaluate the lengths for amino_acids and amino_acids_annotations and

retain the result in a new

listcalled lengths.

- Using logical

operations, test the two values stored in lengths for equivalence and

display the result as a boolean (

TrueorFalse) output.

Conversion to list

As highlighted earlier in this section, arrays in Python can contain any value - regardless of type. We can exploit this feature to extract some interesting information about the data we store in an array.

To that end, we can convert any sequence

to a list. See Table to find out which

of the built-in types in Python are considered to be a sequence.

Suppose we have the sequence for Protein Kinase A Gamma (catalytic) subunit for humans as follows:

PYTHON

# Multiple lines of text may be split into

# several lines inside parentheses:

human_pka_gamma = (

'MAAPAAATAMGNAPAKKDTEQEESVNEFLAKARGDFLYRWGNPAQNTASSDQFERLRTLGMGSFGRVMLV'

'RHQETGGHYAMKILNKQKVVKMKQVEHILNEKRILQAIDFPFLVKLQFSFKDNSYLYLVMEYVPGGEMFS'

'RLQRVGRFSEPHACFYAAQVVLAVQYLHSLDLIHRDLKPENLLIDQQGYLQVTDFGFAKRVKGRTWTLCG'

'TPEYLAPEIILSKGYNKAVDWWALGVLIYEMAVGFPPFYADQPIQIYEKIVSGRVRFPSKLSSDLKDLLR'

'SLLQVDLTKRFGNLRNGVGDIKNHKWFATTSWIAIYEKKVEAPFIPKYTGPGDASNFDDYEEEELRISIN'

'EKCAKEFSEF'

)

print(type(human_pka_gamma))OUTPUT

<class 'str'>We can now convert our sequence from its original type of

str to list by using list() as a

function. Doing so will automatically decompose the text down

into individual characters:

PYTHON

# The function "list" may be used to convert string

# variables into a list of characters:

pka_list = list(human_pka_gamma)

print(pka_list)OUTPUT

['M', 'A', 'A', 'P', 'A', 'A', 'A', 'T', 'A', 'M', 'G', 'N', 'A', 'P', 'A', 'K', 'K', 'D', 'T', 'E', 'Q', 'E', 'E', 'S', 'V', 'N', 'E', 'F', 'L', 'A', 'K', 'A', 'R', 'G', 'D', 'F', 'L', 'Y', 'R', 'W', 'G', 'N', 'P', 'A', 'Q', 'N', 'T', 'A', 'S', 'S', 'D', 'Q', 'F', 'E', 'R', 'L', 'R', 'T', 'L', 'G', 'M', 'G', 'S', 'F', 'G', 'R', 'V', 'M', 'L', 'V', 'R', 'H', 'Q', 'E', 'T', 'G', 'G', 'H', 'Y', 'A', 'M', 'K', 'I', 'L', 'N', 'K', 'Q', 'K', 'V', 'V', 'K', 'M', 'K', 'Q', 'V', 'E', 'H', 'I', 'L', 'N', 'E', 'K', 'R', 'I', 'L', 'Q', 'A', 'I', 'D', 'F', 'P', 'F', 'L', 'V', 'K', 'L', 'Q', 'F', 'S', 'F', 'K', 'D', 'N', 'S', 'Y', 'L', 'Y', 'L', 'V', 'M', 'E', 'Y', 'V', 'P', 'G', 'G', 'E', 'M', 'F', 'S', 'R', 'L', 'Q', 'R', 'V', 'G', 'R', 'F', 'S', 'E', 'P', 'H', 'A', 'C', 'F', 'Y', 'A', 'A', 'Q', 'V', 'V', 'L', 'A', 'V', 'Q', 'Y', 'L', 'H', 'S', 'L', 'D', 'L', 'I', 'H', 'R', 'D', 'L', 'K', 'P', 'E', 'N', 'L', 'L', 'I', 'D', 'Q', 'Q', 'G', 'Y', 'L', 'Q', 'V', 'T', 'D', 'F', 'G', 'F', 'A', 'K', 'R', 'V', 'K', 'G', 'R', 'T', 'W', 'T', 'L', 'C', 'G', 'T', 'P', 'E', 'Y', 'L', 'A', 'P', 'E', 'I', 'I', 'L', 'S', 'K', 'G', 'Y', 'N', 'K', 'A', 'V', 'D', 'W', 'W', 'A', 'L', 'G', 'V', 'L', 'I', 'Y', 'E', 'M', 'A', 'V', 'G', 'F', 'P', 'P', 'F', 'Y', 'A', 'D', 'Q', 'P', 'I', 'Q', 'I', 'Y', 'E', 'K', 'I', 'V', 'S', 'G', 'R', 'V', 'R', 'F', 'P', 'S', 'K', 'L', 'S', 'S', 'D', 'L', 'K', 'D', 'L', 'L', 'R', 'S', 'L', 'L', 'Q', 'V', 'D', 'L', 'T', 'K', 'R', 'F', 'G', 'N', 'L', 'R', 'N', 'G', 'V', 'G', 'D', 'I', 'K', 'N', 'H', 'K', 'W', 'F', 'A', 'T', 'T', 'S', 'W', 'I', 'A', 'I', 'Y', 'E', 'K', 'K', 'V', 'E', 'A', 'P', 'F', 'I', 'P', 'K', 'Y', 'T', 'G', 'P', 'G', 'D', 'A', 'S', 'N', 'F', 'D', 'D', 'Y', 'E', 'E', 'E', 'E', 'L', 'R', 'I', 'S', 'I', 'N', 'E', 'K', 'C', 'A', 'K', 'E', 'F', 'S', 'E', 'F']Practice Exercise 12

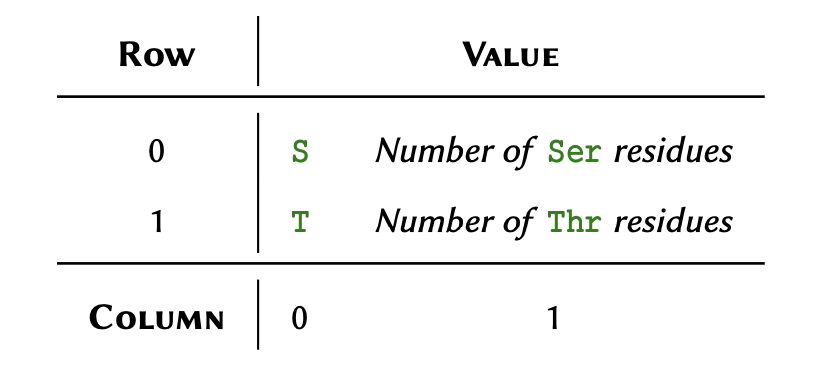

Ask the user to enter a sequence of single-letter amino acids in

lower case. Convert the sequence to list and:

- Count the number of serine and threonine residues and display the result in the following format:

Total number of serine residues: XX

Total number of threonine residues: XX- Check whether or not the sequence contains both serine and threonine residues:

- If it does, display:

The sequence contains both serine and threonine residues.- if it does not, display:

The sequence does not contain both serine and threonine residues.sequence_str = input('Please enter a sequence of signle-letter amino acids in lower-case: ')

sequence = list(sequence_str)

ser_count = sequence.count('s')

thr_count = sequence.count('t')

print('Total number of serine residues:', ser_count)

print('Total number of threonine residues:', thr_count)if ser_count > 0 and thr_count > 0:

response_state = ''

else:

response_state = 'not'

print(

'The sequence does',

'response_state',

'contain both serine and threonine residues.'

)Advanced Topic

Generators represent a specific type in Python whose results are not immediately evaluated. A generator is a specific type of iterable (an object capable of returning elements, one at a time), that can return its items, lazily. This means that it generates values on the fly, and only as and when required in your program. Generators can be particularly useful when working with large datasets, where loading all the data into memory can be computationally expensive. Using genarators with such data, can help to process it in more manageable units.

Generators’ lazy evaluation in functional

programming is often used in the context of a for-loop:

which we will explore in a later L2D lesson on iterations. We do not

further explore generators on this course, but if you are interested to

learn more, you can find plenty of information in the following

official documentation.

Useful methods

Data Structures: More on Lists

In this subsection, we will be reviewing some of the useful and

important methods that are associated with object of type

list. We will make use of snippets of code that exemplify

such methods, in practice. The linked cheatsheet of the methods associated

with the built-in arrays in Python can be helpful.

The methods outlined here are not individually described; however, at this point, you should be able to work out what they do by looking at their names and respective examples.

Count a specific value within a list:

OUTPUT

3Extend a list:

PYTHON

table_a = [1, 2, 2, 2]

table_b = [15, 16]

table_c = table_a.copy() # deep copy.

table_c.extend(table_b)

print(table_a, table_b, table_c)OUTPUT

[1, 2, 2, 2] [15, 16] [1, 2, 2, 2, 15, 16]Extend a list by adding two lists to each other. Note:

adding two lists to each other is not considered an in-place

operation:

PYTHON

table_a = [1, 2, 2, 2]

table_b = [15, 16]

table_c = table_a + table_b

print(table_a, table_b, table_c)OUTPUT

[1, 2, 2, 2] [15, 16] [1, 2, 2, 2, 15, 16]PYTHON

table_a = [1, 2, 2, 2]

table_b = [15, 16]

table_c = table_a.copy() # deep copy.

table_d = table_a + table_b

print(table_c == table_d)OUTPUT

False

We can also reverse the values in a list. There are two

methods for doing so. Being a generator means that the output of the

function is not evaluated immediately; and instead, we get a generic

output. The first of these two methods is:

- Through an in-place operation using .reverse()

OUTPUT

Reversed: [16, 15, 2, 2, 2, 1]- And secondly, using reversed() - which is a built-in generator function.

PYTHON

table = [1, 2, 2, 2, 15, 16]

table_rev = reversed(table)

print("Result:", table_rev)

print("Type:", type(table_rev))OUTPUT

Result: <list_reverseiterator object at 0x7f951f886590>

Type: <class 'list_reverseiterator'>We can, however, force the evaluation process by converting the

generator results into a list:

OUTPUT

Evaluated: [16, 15, 2, 2, 2, 1]Members of a list may also be sorted in-place, as

follows:

OUTPUT

Sorted (ascending): [1, 2, 2, 2, 15, 16]Advanced Topic

There is also a further function built into Python: sorted(). This works in a similar manner to reversed(). Also a generator function, it offers more advanced features that are beyond the scope of this course. You can find out more about it from the official documentation and examples.

The .sort() method takes an optional keyword argument

entitled reverse (default: False). If set to

True, the method will perform a descending sort:

OUTPUT

Sorted (descending): [16, 15, 2, 2, 2, 1]We can also create an empty list, so that we can add

members to it later in our code using .append(), or

.extend() or other tools:

OUTPUT

[]OUTPUT

[5]OUTPUT

['Jane', 'Janette']Practice Exercise 13

Create a list, and experiment with each of the methods

provided in the above example. Try including members of different

types in your list, and see how each of these

methods behave.

This practice exercise was intended to encourage you to experiment with the methods outlined.

Nested Arrays

At this point, you should be comfortable with creating, handling and

manipulating arrays of type list, in Python. It is

important to have a foundational understanding of the principles

outlined in this section so far, before starting to learn about

nested arrays.

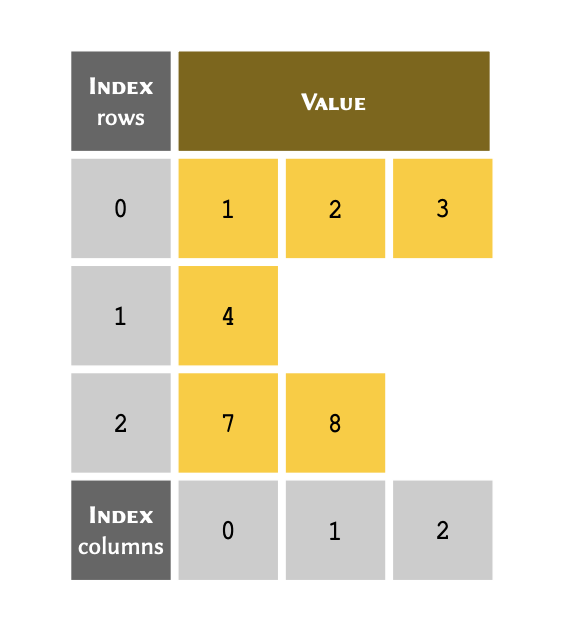

We have already established that arrays can contain any value - regardless of type. This means that they can also contain other arrays. An array that includes at least one member that is, itself, an array is referred to as a nested array. This can be thought of as a table with more than one column:

Remember

Arrays can contain values of any type. This rule applies to

nested arrays too. We have exclusively included int numbers

in our table in order to simplify the above example.

Implementation

The table can be written in Python as a nested array:

PYTHON

# The list has 3 members, 2 of which

# are arrays of type list:

table = [[1, 2, 3], 4, [7, 8]]

print(table)OUTPUT

[[1, 2, 3], 4, [7, 8]]Indexing

The indexing principles for nested arrays are slightly different to

those we have familiarised with, up to this point. To retrieve an

individual member in a nested list, we always reference the

row index, followed by the column index.

We may visualise the process as follows:

To retrieve an entire row, we only need to include the reference for that row. All the values within the row are referenced, implicitly:

OUTPUT

[1, 2, 3]and to retrieve a specific member, we include the reference for both the row and column:

OUTPUT

2We may also extract slices from a nested array. The protocol is identical to normal arrays, described in the previous section of this lesson on slicing. In nested arrays, however, we may take slices from the columns as well as the rows:

OUTPUT

[[1, 2, 3], 4]OUTPUT

[1, 2]Note that only 2 of the 3 members in table are arrays of type

list:

OUTPUT

[1, 2, 3] <class 'list'>OUTPUT

[7, 8] <class 'list'>However, there is another member that is not an array:

OUTPUT

4 <class 'int'>In most circumstances, we would want all the members in an array to be homogeneous in type — i.e. we want them all to have the same type. In such cases, we can implement the table as:

OUTPUT

[4] <class 'list'>An array with only one member — e.g. [4], is sometimes referred to as a singleton array.

Practice Exercise 14

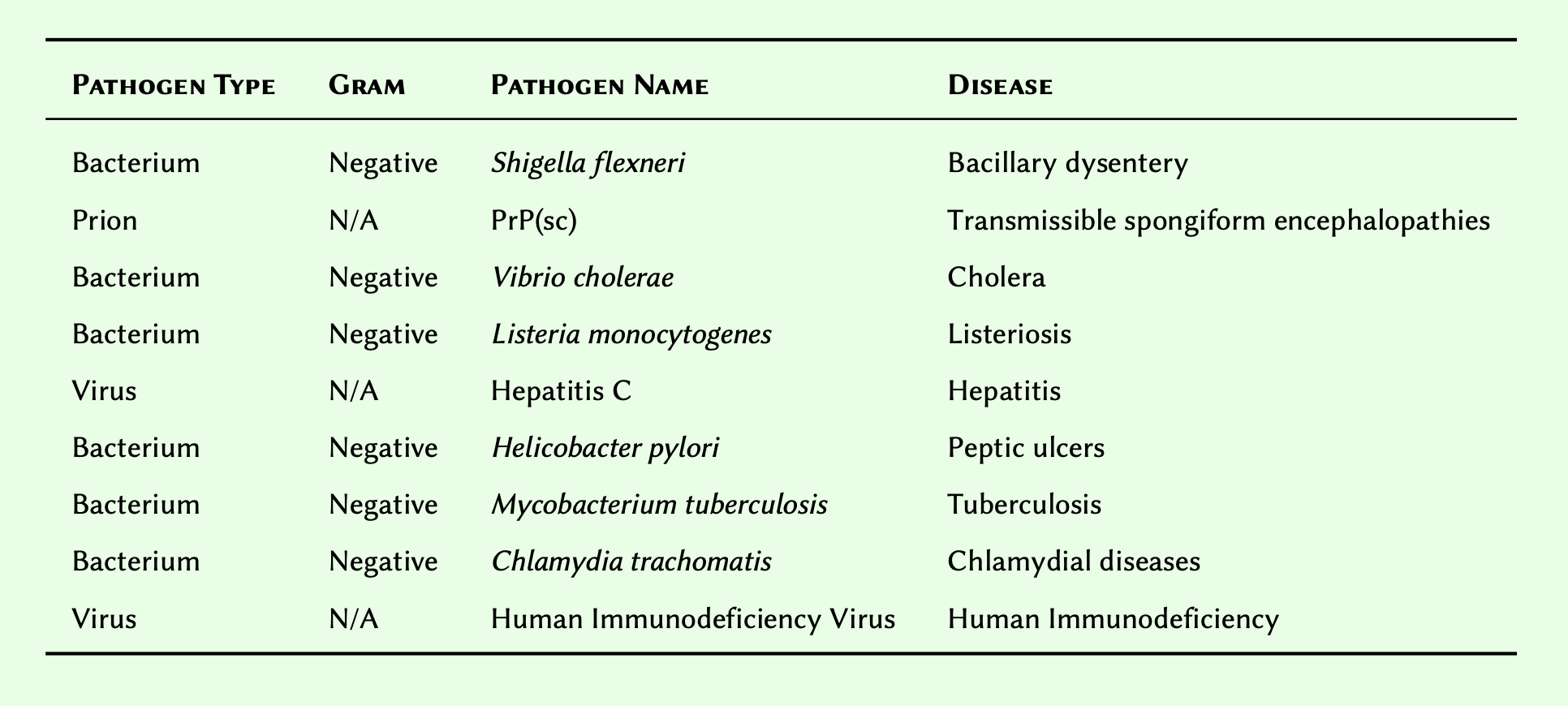

Given the following Table of pathogens and their corresponding diseases:

- Substitute N/A for

None, and create an array to represent the table in its presented order. Retain the array in a variable, and display the result.

- Modify the array you created so that its members are sorted descendingly, and display the result.

PYTHON

disease_pathogen = [

["Bacterium", "Negative", "Shigella flexneri" , "Bacillary dysentery"],

["Prion", None, "PrP(sc)", "Transmissible spongiform encephalopathies"],

["Bacterium", "Negative", "Vibrio cholerae", "Cholera"],

["Bacterium", "Negative", "Listeria monocytogenes", "Listeriosis"],

["Virus", None, "Hepatitis C", "Hepatitis"],

["Bacterium", "Negative", "Helicobacter pylori", "Peptic ulcers"],

["Bacterium", "Negative", "Mycobacterium tuberculosis", "Tuberculosis"],

["Bacterium", "Negative", "Chlamydia trachomatis", "Chlamydial diseases"],

["Virus", None, "Human Immunodeficiency Virus", "Human Immunodeficiency"]

]

print(disease_pathogen)OUTPUT

[['Bacterium', 'Negative', 'Shigella flexneri', 'Bacillary dysentery'], ['Prion', None, 'PrP(sc)', 'Transmissible spongiform encephalopathies'], ['Bacterium', 'Negative', 'Vibrio cholerae', 'Cholera'], ['Bacterium', 'Negative', 'Listeria monocytogenes', 'Listeriosis'], ['Virus', None, 'Hepatitis C', 'Hepatitis'], ['Bacterium', 'Negative', 'Helicobacter pylori', 'Peptic ulcers'], ['Bacterium', 'Negative', 'Mycobacterium tuberculosis', 'Tuberculosis'], ['Bacterium', 'Negative', 'Chlamydia trachomatis', 'Chlamydial diseases'], ['Virus', None, 'Human Immunodeficiency Virus', 'Human Immunodeficiency']]OUTPUT

[['Virus', None, 'Human Immunodeficiency Virus', 'Human Immunodeficiency'], ['Virus', None, 'Hepatitis C', 'Hepatitis'], ['Prion', None, 'PrP(sc)', 'Transmissible spongiform encephalopathies'], ['Bacterium', 'Negative', 'Vibrio cholerae', 'Cholera'], ['Bacterium', 'Negative', 'Shigella flexneri', 'Bacillary dysentery'], ['Bacterium', 'Negative', 'Mycobacterium tuberculosis', 'Tuberculosis'], ['Bacterium', 'Negative', 'Listeria monocytogenes', 'Listeriosis'], ['Bacterium', 'Negative', 'Helicobacter pylori', 'Peptic ulcers'], ['Bacterium', 'Negative', 'Chlamydia trachomatis', 'Chlamydial diseases']]Dimensions

A nested array is considered two-dimensional or 2D when:

All of its members in a nested array are arrays, themselves;

All sub-arrays are of equal length — i.e. all the columns in the table are filled and have the same number of rows; and,

All members of the sub-arrays are homogeneous in type — i.e. they all have the same type (e.g.

int).

A two dimensional arrays may be visualised as follows:

Advanced Topic

Nested arrays may, themselves, be nested. This means that, if needed, we can have 3, 4 or n dimensional arrays, too. Analysis and organisation of such arrays is an important part of a field known as optimisation in computer science and mathematics. Optimisation is the cornerstone of machine learning, and addresses the problem known as curse of dimensionality.

Such arrays are referred to in mathematics as a matrix. We can therefore represent a two-dimensional array as a mathematical matrix. To that end, the above array would translate to the annotation displayed in equation below.

\[table=\begin{bmatrix} 1&2&3\\ 4&5&6\\ 7&8&9\\ \end{bmatrix}\]

The implementation of these arrays is identical to the implementation of other nested arrays. We can therefore code our table in Python as:

OUTPUT

[[1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6], [7, 8, 9]]OUTPUT

[7, 8, 9]OUTPUT

4OUTPUT

[[1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6]]Practice Exercise 15

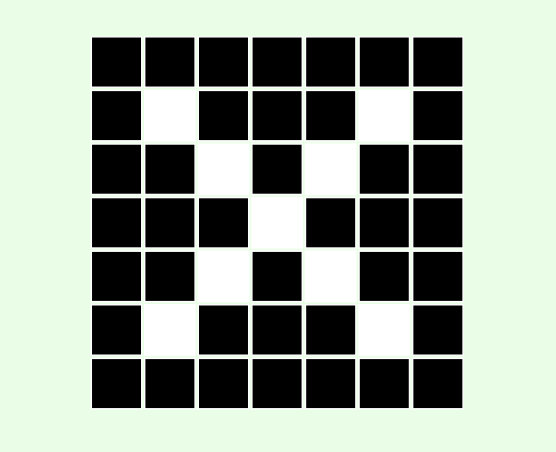

Computers see images as multidimensional arrays (matrices). In its simplest form, an image is a two-dimensional array containing only two colours.

Given the following black and white image:

- Considering that black and white squares represent zeros and ones respectively, create a two-dimensional array to represent the image. Display the results.

- Create a new array, but this time use

FalseandTrueto represent black and white respectively.

Display the results.

PYTHON

cross = [

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0],

[0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0],

[0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]

]

print(cross)OUTPUT

[[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0], [0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0], [0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0], [0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0], [0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]]PYTHON

cross_bool = [

[False, False, False, False, False, False, False],

[False, True, False, False, False, True, False],

[False, False, True, False, True, False, False],

[False, False, False, True, False, False, False],

[False, False, True, False, True, False, False],

[False, True, False, False, False, True, False],

[False, False, False, False, False, False, False]

]

print(cross_bool)OUTPUT

[[False, False, False, False, False, False, False], [False, True, False, False, False, True, False], [False, False, True, False, True, False, False], [False, False, False, True, False, False, False], [False, False, True, False, True, False, False], [False, True, False, False, False, True, False], [False, False, False, False, False, False, False]]Summary

At this point, you should be familiar with arrays and how they work,

in general. Throughout this section, we extensively covered the Python

list, which is one of the language’s most popular types of

built-in arrays. We also learned:

How to

listfrom the scratch;How to manipulate a

listusing different methods;How to use indexing and slicing techniques to our advantage;

Mutability — a concept we revisit in the forthcoming lessons;

In-place operations, and the difference between weak references and deep copies;

Nested and multi-dimensional arrays; and,

How to convert other sequences (e.g.

str) tolist.

Tuple

Data Structures: Tuples and Sequences

Another of Python’s built-in array types is called a tuple.

A tuple is an immutable alternative to list. That is, once

a tuple has been created, its contents cannot be modified in any way.

Tuples are often used in applications where it is imperative that the

contents of an array cannot be changed.

For instance, we know that in the Wnt signaling pathway, there are two co-receptors. This is final, and would not change at any point in our program.

Remember

The most common way to implement a tuple in Python, is

to place our comma-separated values inside round parentheses: (1, 2, 3, …). While there is no

specific theoretical term for a tuple instantiated with round

parentheses, we can refer to this type of tuple as an explicit

tuple.

You can also instantiate a tuple without parentheses, as well: (1, 2, 3, …). In this case, Python acknowledges that a tuple is implied, and is therefore assumed. Thus, we often refer to this type of tuple as an implicit tuple, and these are created using an operation called packing.

For the time being, we will be making use of explicit tuples, as they are the clearest and most explicit in annotation, and therefore easiest to program with and recognise.

Similarly, we can briefly demonstrate that removing round parentheses, or instantiating a implicit tuple, is categorised in the same way, in Python:

OUTPUT

<class 'tuple'>OUTPUT

('Frizzled', 'LRP')OUTPUT

<class 'tuple'>OUTPUT

('Wnt Signaling', ('Frizzled', 'LRP'))OUTPUT

Wnt Signaling

Indexing and slicing principles for a tuple are identical

to those of a list, aforementioned in this lesson’s

subsections on indexing and slicing.

Conversion to tuple

Similar to list, we can convert other sequences to

tuple:

OUTPUT

<class 'list'>OUTPUT

(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)OUTPUT

<class 'tuple'>OUTPUT

<class 'str'>OUTPUT

('T', 'h', 'i', 's', ' ', 'i', 's', ' ', 'a', ' ', 's', 't', 'r', 'i', 'n', 'g', '.')OUTPUT

<class 'tuple'>Immutability

In contrast with list, however, if we attempt to change

the contents of a tuple, a TypeError is

raised:

OUTPUT

TypeError: 'tuple' object does not support item assignmentEven though tuple is an immutable type, it can contain

both mutable and immutable objects:

PYTHON

# (immutable, immutable, immutable, mutable)

mixed_tuple = (1, 2.5, 'abc', (3, 4), [5, 6])

print(mixed_tuple)OUTPUT

(1, 2.5, 'abc', (3, 4), [5, 6])and mutable objects inside a tuple may still be

changed:

OUTPUT

(1, 2.5, 'abc', (3, 4), [5, 6]) <class 'tuple'>OUTPUT

[5, 6] <class 'list'>Advanced Topic

Why and how can we change mutable objects inside a tuple,

when a tuple is considered to be an immutable data

structure:

Members of a tuple are not directly stored in memory. An

immutable value (e.g. an integer: int) has an

existing, predefined reference, in memory. When used in a

tuple, it is this reference that is associated

with the tuple, and not the value itself. On the other

hand, a mutable object does not have a predefined reference in memory,

and is instead created on request somewhere in your computer’s memory

(wherever there is enough free space).

tuple, remains identical. In Python, it is possible to

discover the reference an object is using, with the function

id(). Upon experimenting with this function, you will

notice that the reference to an immutable object (e.g. an

int value) will never change, no matter how many times you

define it in a different context or variable. In contrast, the reference

number to a mutable object (e.g. a list) is

changed every time it is defined, even if it contains exactly the same

values.

OUTPUT

(1, 2.5, 'abc', (3, 4), [5, 15])OUTPUT

(1, 2.5, 'abc', (3, 4), [5, 15, 25])PYTHON

# We cannot remove the list from the tuple,

# but we can empty it by clearing its members:

mixed_tuple[4].clear()

print(mixed_tuple)OUTPUT

(1, 2.5, 'abc', (3, 4), [])Tuples may be empty or have a single value (singleton):

OUTPUT

() <class 'tuple'> 0PYTHON

# Empty parentheses also generate an empty tuple.

# Remember: we cannot add values to an empty tuple, later.

member_b = ()

print(member_b, type(member_b), len(member_b))OUTPUT

() <class 'tuple'> 0PYTHON

# Singleton - Note that it is essential to include

# a comma after the value in a single-member tuple:

member_c = ('John Doe',)

print(member_c, type(member_c), len(member_c))OUTPUT

('John Doe',) <class 'tuple'> 1PYTHON

# If the comma is not included, a singleton tuple

# is not constructed:

member_d = ('John Doe')

print(member_d, type(member_d), len(member_d))OUTPUT

John Doe <class 'str'> 8Packing and unpacking

As previously discussed, a tuple may also be constructed

without parentheses. This is an implicit operation and is known as

packing.

Remember

Implicit processes must be used sparingly. As always, the more coherent the code, the better it is.

OUTPUT

(1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 11) <class 'tuple'> 6PYTHON

# Note that for a singleton, we still need to

# include the comma.

member = 'John Doe',

print(member, type(member), len(member))OUTPUT

('John Doe',) <class 'tuple'> 1The reverse of this process is known as unpacking. Unpacking is no longer considered an implicit process because it replaces unnamed values inside an array, with named variables:

OUTPUT

14OUTPUT

14 17PYTHON

member = ('Jane Doe', 28, 'London', 'Student', 'Female')

name, age, city, status, gender = member

print('Name:', name, '- Age:', age)OUTPUT

Name: Jane Doe - Age: 28Note

There is another type of tuple in Python referred to as a

namedtuple. This allows for the members of a

tuple to be named independently (e.g.

member.name or member.age), and thereby

eliminates the need for unpacking. It was originally implemented by Raymond Hettinger, one of

Python’s core developers, for Python 2.4 (in 2004) but was neglected at

the time. It has since gained popularity as a very useful tool.

namedtuple is not a built-in tool, so it is not discussed

here. However, it is included in the default library and is installed as

a part of Python. If you are feeling ambitious and would like to learn

more, please take a look at the official

documentations and examples. Raymond is also a regular speaker at

PyCon (International Python Conferences), recordings of which are

available online. He also often uses his Twitter/X account to talk about

small, but important features in Python; which could be worth throwing

him a follow.

Summary

In this section of our Basic Python 2 lesson, we learned about

tuple - another type of built-in array within Python, and

one which is immutable. This means that once it is created, the

array can no longer be altered. We saw that trying to change the value

of a tuple raises a TypeError. We also

established that list and tuple follow an

identical indexing protocol, and that they have 2 methods in common:

.index()() and .count(). Finally, we talked about

packing and unpacking techniques, and how they improve

the quality and legibility of our code.

If you are interested in learning about list and

tuple in more depth, have a look at the official

documentation of Sequence Types – list, tuple, range.

Interesting Fact

Graph theory was initially developed by the renowned Swiss mathematician and logician Leonhard Euler (1707 – 1783). Howeve graphs, in the sense discussed here, were introduced by the English mathematician James Joseph Sylvester (1814 – 1897).

Exercises

End of chapter Exercises

- We have

table = [[1, 2, 3], ['a', 'b'], [1.5, 'b', 4], [2]]What is the length of table and why?

Store your answer in a variable and display it using print().

- Given the sequence for the Gamma (catalytic) subunit of the Protein Kinase A as:

human_pka_gamma = (

'MAAPAAATAMGNAPAKKDTEQEESVNEFLAKARGDFLYRWGNPAQNTASSDQFERLRTLGMGSFGRVML'

'VRHQETGGHYAMKILNKQKVVKMKQVEHILNEKRILQAIDFPFLVKLQFSFKDNSYLYLVMEYVPGGEM'

'FSRLQRVGRFSEPHACFYAAQVVLAVQYLHSLDLIHRDLKPENLLIDQQGYLQVTDFGFAKRVKGRTWT'

'LCGTPEYLAPEIILSKGYNKAVDWWALGVLIYEMAVGFPPFYADQPIQIYEKIVSGRVRFPSKLSSDLK'

'DLLRSLLQVDLTKRFGNLRNGVGDIKNHKWFATTSWIAIYEKKVEAPFIPKYTGPGDASNFDDYEEEEL'

'RISINEKCAKEFSEF'

)Using the sequence;

Work out and display the number of Serine (S) residues.

Work out and display the number of Threonine (T) residues.

Calculate and display the total number of Serine and Threonine residues in the following format:

Serine: X

Threonine: X- Create a nested array to represent the following table, and call it :

Explain why in the previous question, we used the term nested instead of two-dimensional in reference to the array? Store your answer in a variable and display it using print().

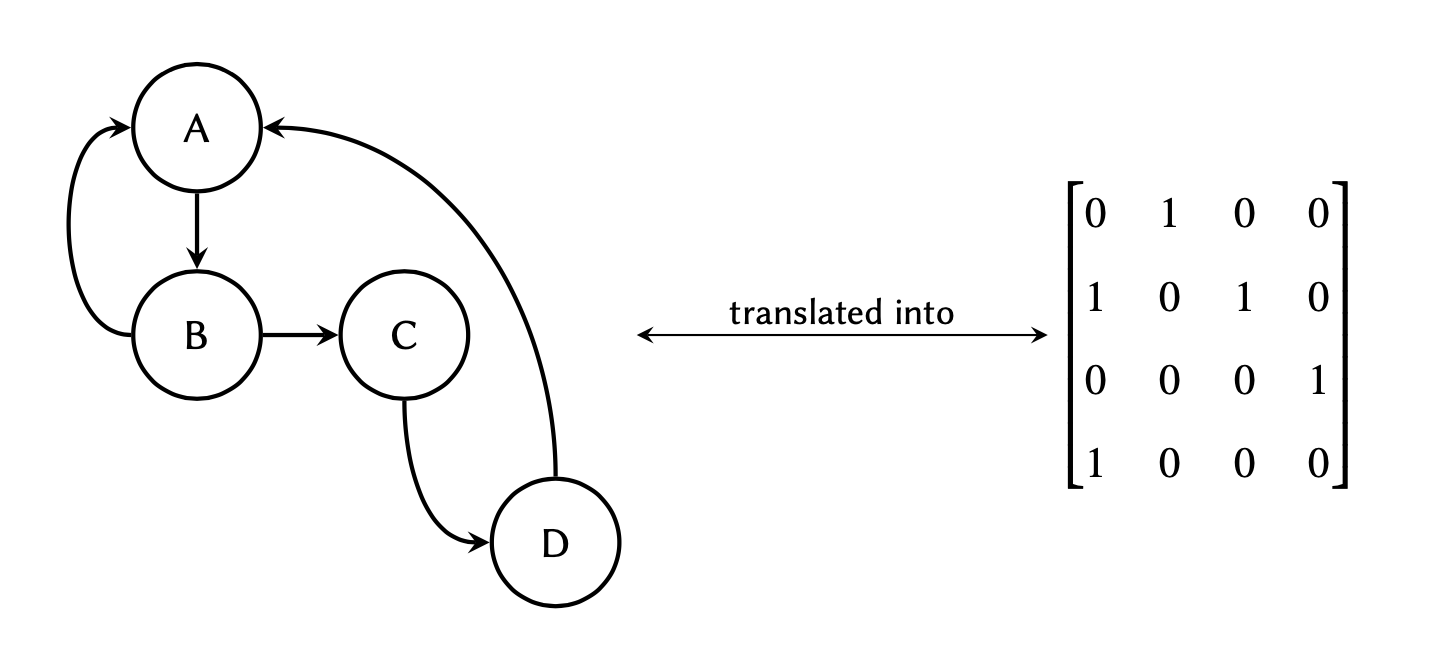

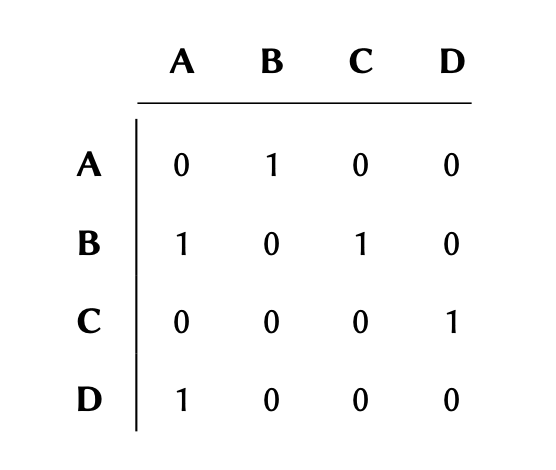

Graph theory is a prime object of discrete mathematics utilised for the non-linear analyses of data. The theory is extensively used in systems biology, and is gaining momentum in bioinformatics too. In essence, a graph is a structure that represents a set of object (nodes) and the connections between them (edges).

The aforementioned connections are described using a special binary (zero and one) matrix known as the adjacency matrix. The elements of this matrix indicate whether or not a pair of nodes in the graph are adjacent to one another.

where each row in the matrix

represents a node of origin in the graph, and each column a node of

destination:

where each row in the matrix

represents a node of origin in the graph, and each column a node of

destination:

If the graph maintains a

connection (edge) between two nodes (e.g. between nodes A and B in the graph above), the

corresponding value between those nodes would be #1 in the matrix, and

if there are no connections, the corresponding value would #0.

If the graph maintains a

connection (edge) between two nodes (e.g. between nodes A and B in the graph above), the

corresponding value between those nodes would be #1 in the matrix, and

if there are no connections, the corresponding value would #0.

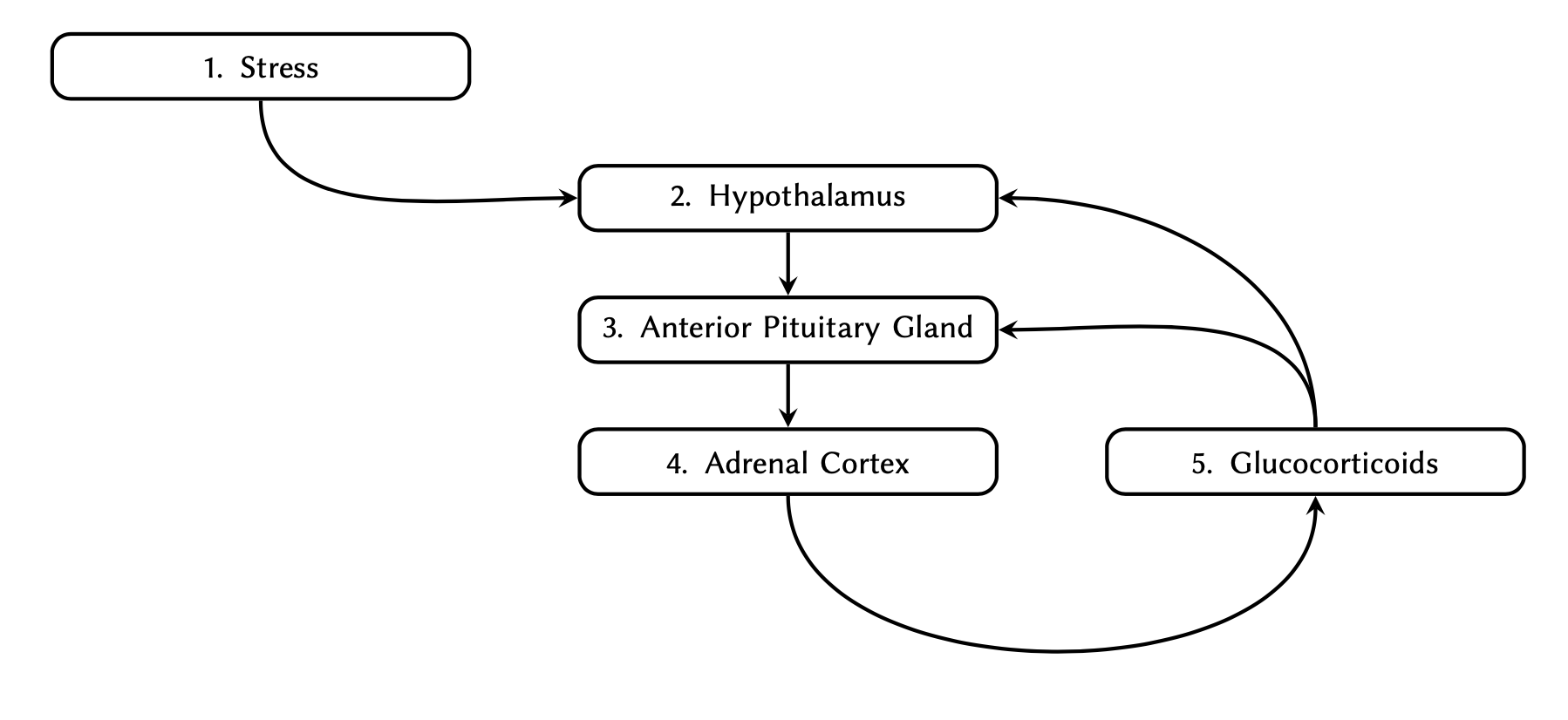

Given the following graph:

Determine the adjacency matrix and implement it as a two-dimensional array in Python. Display the final array.

Key Points

-

listsandtuplesare 2 types of arrays. - An index is a unique reference to a specific value and Python uses a zero-based indexing system.

-

listsare mutable because their contents can be modified. - slice(), .pop(), .index(), .remove() and .insert() are some of the key functions used in mutable arrays.

-

tuplesare immutable, which means that their contents cannot be modified.